By: Duke Mwedzi

The introduction of a new presidential administration has brought with it a flurry of executive orders. Among them was an order “Reevaluating and realigning United States Foreign Aid”, which paused federal funding for foreign aid [1]. This includes the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), whose very existence appears increasingly uncertain amid explicit threats to shut it down completely [2]. USAID is the world’s largest single aid donor, operating a budget of over $50 billion and has been responsible for some important strides in improving the human condition [3], [4]. For example, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) saved an estimated 25 million lives and reducing AIDS related deaths by 59% globally [5], [6]. USAID has also overhauled collection of social statistics in low-income countries through the Demographic and Health Surveys, which would become a leading source of data for development-oriented researchers in population science, public health, and nutrition [7].

Despite these successes, major figures in the Trump administration see American aid to foreign as inefficient and wasteful of American resources in their efforts to reduce administrative bloat. This position may not be unpopular domestically, with polling research showing that roughly half of Americans want to reduce economic spending in other countries [8]. Though it would achieve this goal, the scale and potential consequences of shutting down USAID would be unprecedented.

This would not be the first time that questions have been raised about development initiatives and their effectiveness. Among social scientists, organisations like USAID and what they represent have long been targets of criticism due to their role in upholding Western imperialism and perpetuating dependence of poor countries on foreign aid, rather than addressing the root causes of poverty. For instance, following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the US government disbursed $3 billion in aid, but only 1% of it went to the Haitian government [9], [10]. The vast majority of aid went to American-based private contractors, strengthening the US position, undermining the Haitian government, and continuing their economic dependence on the US. Similar cases across the developing world have led to sharp critiques of international development and suspicion around the true motives of powerful countries. Some critics have called for an end to the very concept of international development altogether, preferring a community-based, grassroots approach that isn’t tied to endless economic growth and its accompanying environmental degradation [11].

However, what is often lost in these debates is the will of people in developing countries. How do ordinary people in low-income countries view development? Do they share the critiques, or do they view foreign intervention as a necessary step towards improving their conditions? Ultimately, what kind of development do people want for their own communities: a top down, centrally organised approach or a more modest, localised strategy? These are the questions I looked to answer during my Master’s thesis. I used 2021 survey data from Afrobarometer which included nationally representative samples of over 14 000 respondents in 11 countries in Southern Africa, a somewhat under-researched region on the continent. Results showed that public opinion is largely in line with conventional development, implying that organisations like USAID still have an important role to play in the eyes of the world.

What are the problems in developing countries?

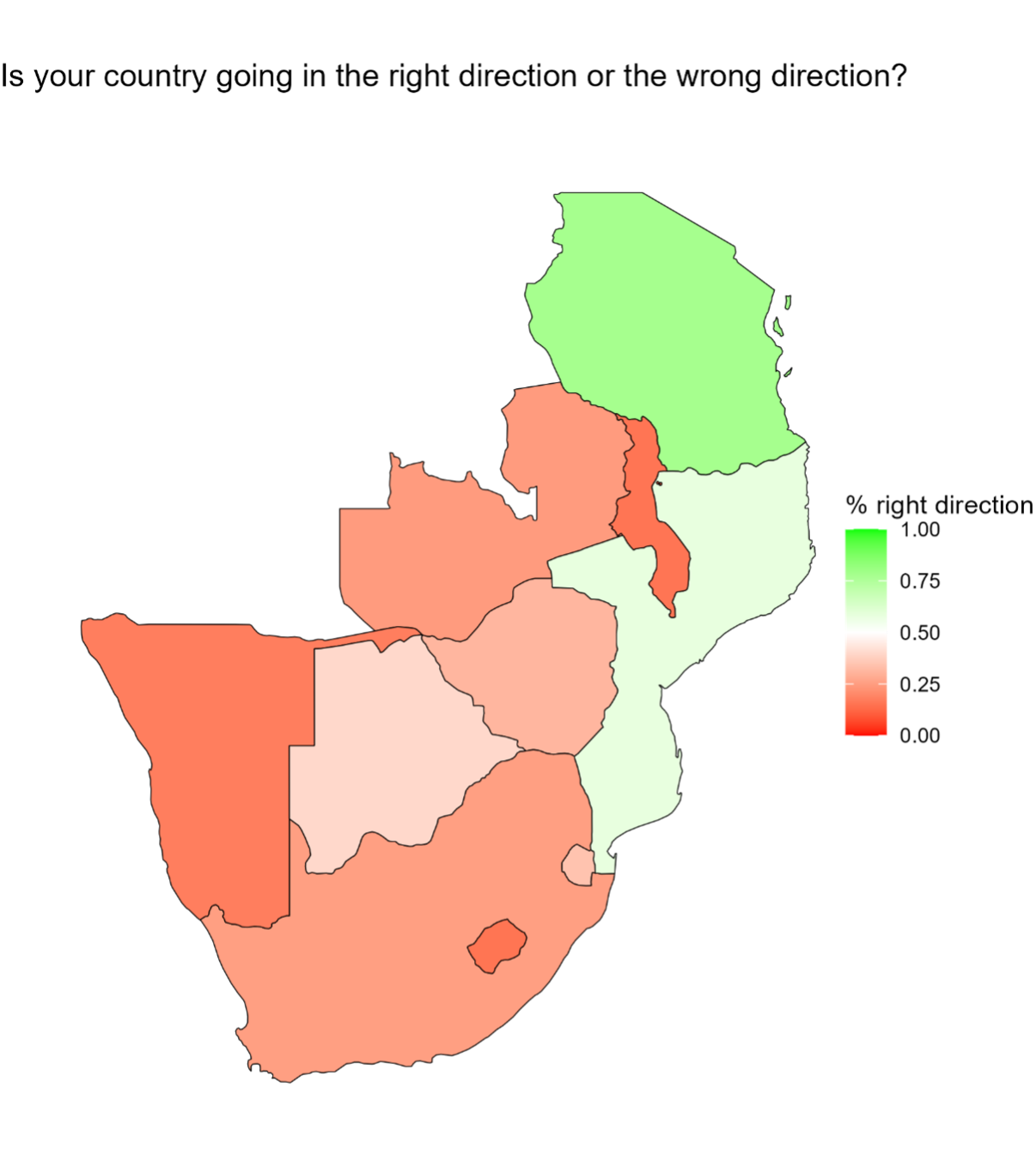

Should we even bother with development at all? It is often taken for granted that low-income countries are on a negative trajectory, which then becomes the justification for intervention and development. To address this, respondents were asked, “Is your country going in the right direction or the wrong direction?” In every country except Tanzania and Mozambique, the majority of people said that their country is going in the wrong direction. Lesotho and Malawi had the most negative responses, with 85% and 84% respectively saying that their country is going in the wrong direction.

As part of interventions to move countries in the right direction, international development organisations like USAID, the UN and the World Bank typically focus on material conditions. They prioritise concerns like improving nutrition, access to safe drinking water, reducing malaria, and, increasingly, equitable distribution of these goods along gender lines. This orientation appears consistent with the concerns of people in Southern Africa. When asked, “What is the biggest problem facing your country?,” the most frequent responses included water supply, health, and poverty, but also socioeconomic issues like unemployment and education.

| Top 10 responses: What is the biggest problem in your country? | ||

| Response | Freq. | Percent |

| Unemployment | 2,996 | 21 |

| Water supply | 1,293 | 9 |

| Infrastructure / roads | 1,246 | 9 |

| Health | 1,149 | 8 |

| Poverty/destitution | 889 | 6 |

| Education | 880 | 6. |

| Food shortage/famine | 792 | 6 |

| Management of the economy | 722 | 5 |

| Corruption | 699 | 5 |

| Crime and Security | 614 | 4 |

Moving from problems to solutions

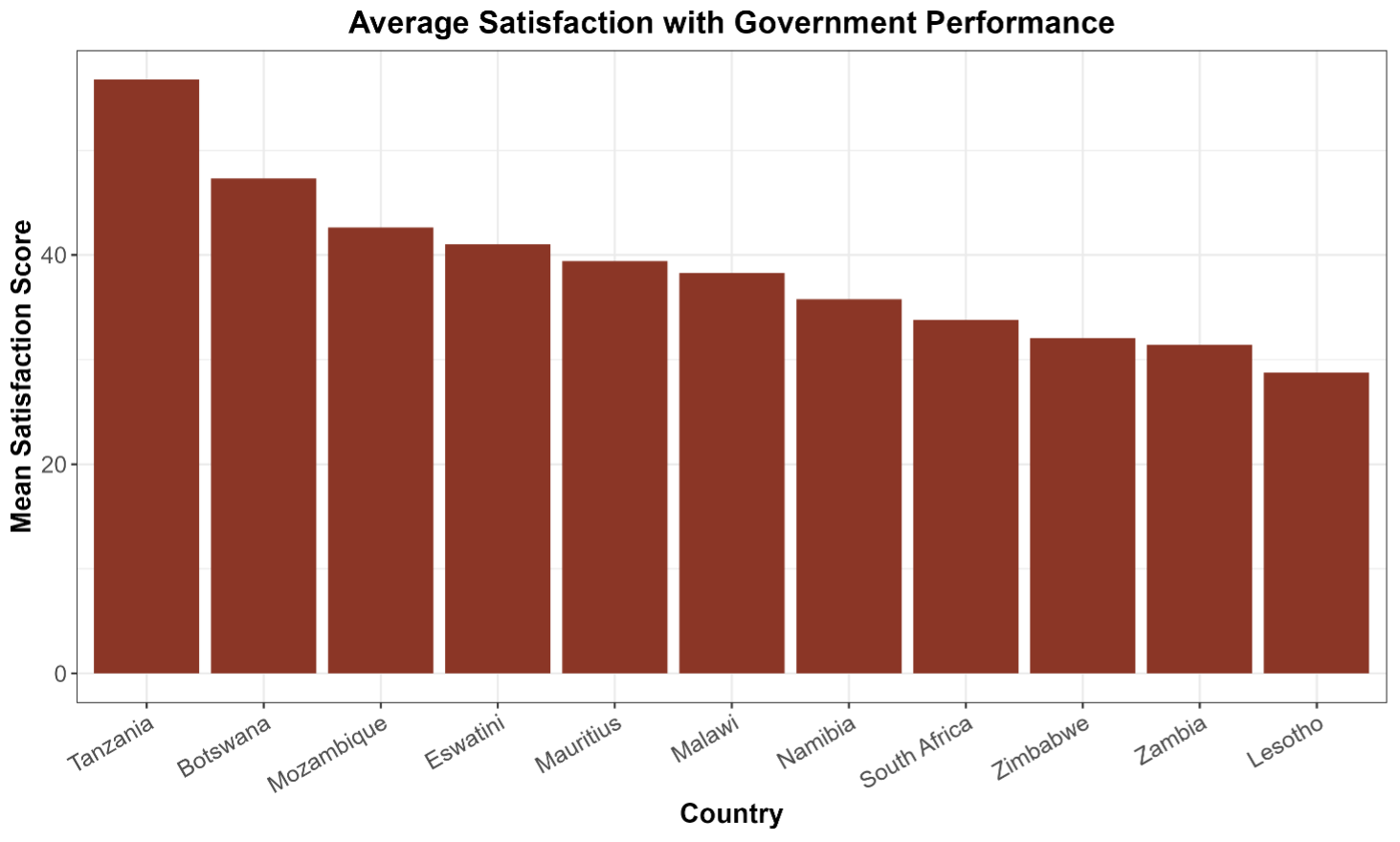

The next question is, since people have identified these problems in their communities, who should be responsible for solving them? Ordinarily, this would be the mandate of the government, but people in low-income countries show low levels of confidence in their leaders. I created a factor based on 15 questions asking people how their government is handling various responsibilities, such as reducing poverty, improving healthcare, and providing water and sanitation services. The factor is on a scale from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating low satisfaction with government, and higher scores indicating high satisfaction. All countries except Tanzania are below 50, suggesting low levels of satisfaction across the region with how their national governments are performing. People have identified problems in their countries, but do not feel confident that their governments are addressing them.

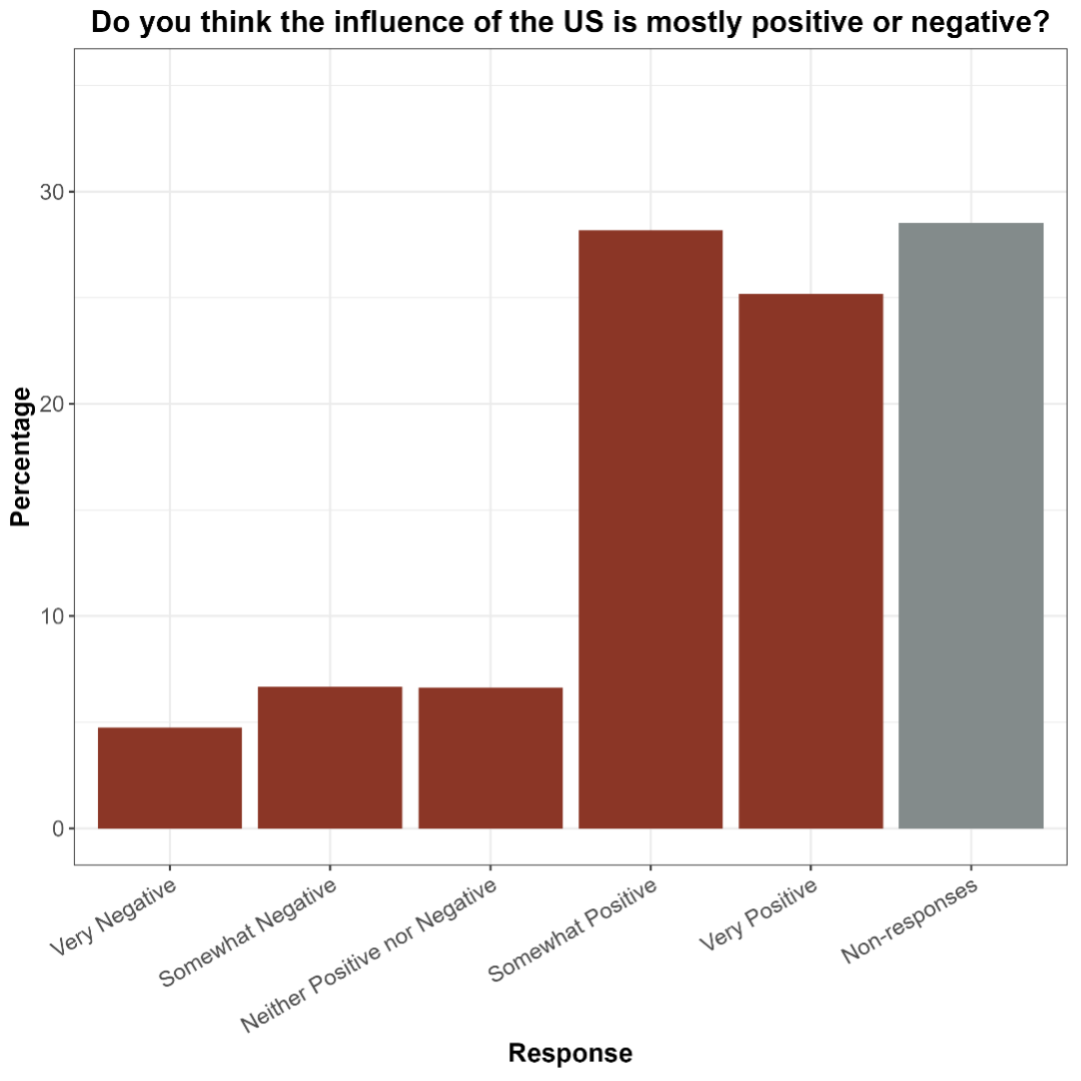

If governments are unable to address citizens’ concerns, another approach might be turning to the international community for support. Afrobarometer does not ask specifically about USAID, but there are questions asking whether the overall influence of the United States is positive or negative. This question is also asked for the United Nations and other major world powers. Development aid is often treated with suspicion, but people in Southern Africa appear to hold a much more favourable view: 65% of people in Southern Africa view the influence of the US as somewhat positive or very positive. The UN, another major player in the development sector, is similarly well regarded at 56% of responses viewing their influence as somewhat positive or very positive.

So far, the results show that people see important challenges in their countries, are not satisfied with how their governments are handling them, and take a positive view of US influence and the activities of the UN. However, it is worth pausing to reflect on what development means to people on the ground, and what kind of development they ultimately want. The idea of development is fundamentally a visionary process that goes beyond identifying problems and imagines what the solutions could look like. The spirit of this idea is captured in the question, “What model for development should your country follow?” This question invites respondents to identify what country best typifies the kind of society they would like to live in, and the responses are, again, mostly in line with the approach international development: the most common response was the United States at 25%. South Africa, one of the continent’s economic powerhouses, was second at 22%. Interestingly, the third most common response was China, with 22% of people in Southern Africa saying that China is the model for development that their country should follow. By shutting down USAID and withdrawing from international development, the US may end up ceding ground to their greatest economic and political rival, a threat that has been recognised by some in the Republican Party [12], [13].

Conclusion

There are many pressing and severe problems in Africa. People on the ground are acutely aware of these and do not feel confident that their governments will address them. Through USAID, the US has mobilised their immense capacity to address these issues, though this has also undeniably served American geopolitical interests. Despite this, and despite the new administration’s recent actions, citizens in developing countries view the US as a positive influence in the world and a worthwhile model for development. By shutting down USAID, the US will not only guarantee increased human suffering in the short term, but also leave a power vacuum for other countries to fill in the long term. The US may be the most popular model for development but China is not far behind, and the growing BRICS coalition will certainly be poised to take over. Pausing foreign aid may reduce government spending, but it will come at other significant costs, both for the US and for people in low-income countries.

References

[1] “Reevaluating And Realigning United States Foreign Aid,” The White House. Accessed: Feb. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/reevaluating-and-realigning-united-states-foreign-aid/

[2] “Implementing the President’s Executive Order on Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid,” United States Department of State. Accessed: Feb. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.state.gov/implementing-the-presidents-executive-order-on-reevaluating-and-realigning-united-states-foreign-aid/

[3] D. Shepardson and C. Sanders, “Musk says he is working to shut down ‘beyond repair’ USAID,” Reuters, Feb. 03, 2025. Accessed: Feb. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/world/us/musk-give-update-reform-effort-amid-questions-about-his-power-2025-02-03/

[4] “Agency for International Development (USAID) | Spending Profile | USAspending.” Accessed: Feb. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://usaspending.gov/agency/agency-for-international-development

[5] “PEPFAR Latest Global Results & Projections Factsheet (Dec. 2024),” United States Department of State. Accessed: Feb. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.state.gov/pepfar-latest-global-results-factsheet-dec-2024/

[6] K. K. / AP, “What Is USAID and What Impact Does It Have Across the Globe?,” TIME. Accessed: Feb. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://time.com/7213288/what-is-usaid-what-impact-does-it-have-across-the-globe/

[7] D. J. Corsi, M. Neuman, J. E. Finlay, and S. Subramanian, “Demographic and health surveys: a profile,” International Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 1602–1613, Dec. 2012, doi: 10.1093/ije/dys184.

[8] L. Berry, “Americans Prioritize Domestic Spending over Foreign Aid.” Accessed: Feb. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/americans-prioritize-domestic-spending-over-foreign-aid

[9] B. Hebblethwaite, “How Haiti Became an Aid State,” Foreign Policy. Accessed: Feb. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/02/24/aid-state-johnston-book-review-haiti-usaid-corruption/

[10] V. Ramachandran and J. Walz, “Haiti: Where Has All the Money Gone?,” Journal of Haitian Studies, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 26–65, 2015.

[11] S. Latouche, “Degrowth economics,” Le Monde diplomatique. Accessed: Jun. 28, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://mondediplo.com/2004/11/14latouche

[12] opinion contributor Charlie Dent, “Shuttering USAID is a win for China and a loss for America,” The Hill. Accessed: Feb. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://thehill.com/opinion/5134684-us-agency-foreign-aid-threatened/

[13] S. H. Ward Katy Stech Ferek and Alexander, “Trump’s USAID Shutdown Alarms Republican Allies,” WSJ. Accessed: Feb. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/trumps-usaid-shutdown-alarms-republican-allies-994628df