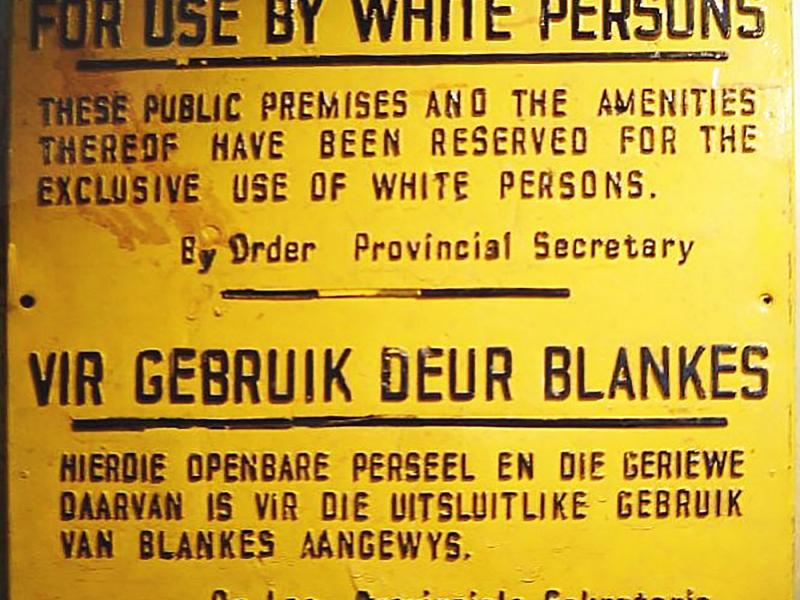

South Africa in the 1980s was a country on the verge of transition. Under increasing pressure from international and domestic opponents of the apartheid regime, and beleaguered by conflicts with neighboring states, the South African regime was inching towards reform. In 1983, the constitution was reformed to allow some non-white minorities (officially classified as “Coloured” and “Indian”) to participate in parliament, while the Black majority was still excluded from central government bodies.[1] Elections for the first Coloured and Indian chambers of parliament were held in 1984. Throughout this period, violence was increasing as the tensions under the apartheid regime grew. Finally, in 1993, a new draft constitution was published, granting all South Africans equal voting rights, and the first elections based on universal suffrage were held in 1994.

Five surveys from Human Sciences Research Council, broken into eight datasets, are now available at the Roper Center in SPSS, Stata, and .csv formats. They offer a rare glimpse into the views and experiences of South Africans at this tumultuous time, from 1982 to 1994. They cover a range of topics, including proposed changes to make the regime more inclusive, non-white citizens’ experiences with their first elections, peace negotiations with South Africa’s neighbors, perceptions of crime and law enforcement in the country, and the transition to democracy. The surveys offer insights into the relationships of different population groups to one another and to the changing regime. While the four surveys from the 1980s are restricted to respondents categorized as “White,” “Coloured,” or “Indian,” the surveys from 1993 and 1994 include datasets with respondents from each of the major population groups, including the majority “Black” or “Bantu” classification.

The topic of race relations receives particular attention, with questions such as “Should Blacks be represented in the new parliament according to their numbers?”, “Can power sharing be implemented in practice as a means of ensuring peace among Whites, Coloureds, and Indians?”, and “Will a few, a lot or none of Whites leave South Africa when the government is no longer white?”. A slim plurality of non-white respondents said in 1984 that Blacks should be represented in parliament according to their numbers. Most respondents indicated in 1993 that they believed many white South Africans would leave the country following the end of apartheid. Other questions focus on respondents’ attitudes toward different aspects of discriminatory legislation under the apartheid regime. For instance, a majority of non-white respondents indicated in 1983 that mixed-race residential areas should be allowed.

Attitudes toward crime and violence are also explored, with questions asking respondents whether they think violence is necessary in order to bring about political change, whether violence will increase after the end of apartheid, and whether sentencing for different crimes is too severe or too lenient. Respondents were evenly split on whether violence would increase or decrease after the end of apartheid. For most types of crimes, a majority felt in 1983 that sentences were too lenient.

Some questions touch on international affairs, asking for respondents’ thoughts on the level of threat Angola and Mozambique pose to South Africa, and whether South Africa should change its internal policies in order to obtain more support abroad for its peace negotiations. A plurality of white respondents indicated in 1984 that Angola and Mozambique would indeed pose a threat to South Africa once their internal problems were resolved. An overwhelming majority of respondents rejected the idea that South Africa should change its internal policies to obtain more international support.

As the country transitioned to democracy, the survey conducted shortly before the 1994 election showed strong support for the African National Congress, which went on to win the election. Respondents were also asked which of their preferred party’s policies they liked most, with many listing “equality for Africans,” “employment,” “education” and “peace” in response.

[1] Under the apartheid regime, the “White” classification was used for descendants of European settlers and immigrants from European countries, the “Indian” or “Asian” classification was used for individuals of Indian descent, the “Coloured” classification was used for individuals with a wide range of mixed-race heritage, and the “Black” or “Bantu” classification was used for individuals of African descent, who constituted the majority group in South Africa.

Nina Obermeier

Nina is a third-year PhD student in the Department of Government at Cornell University. Her research focuses on public opinion toward different aspects of international economic integration and toward global governance. Prior to starting her PhD studies, Nina has worked at a trade association in Brussels and at the University of Oxford.