In 1968, even more so than in most years, the news was bleak – the carnage in Vietnam, race riots, violence in the streets at the Democratic National Convention.

But perhaps nothing was as shocking as the assassinations in quick succession of first civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., then Democratic presidential candidate Senator Robert Kennedy. Opinion polls from the Roper collection document public views of King and Kennedy before their murders and the public response to these tragedies of 1968.

Shot rings out in the Memphis sky

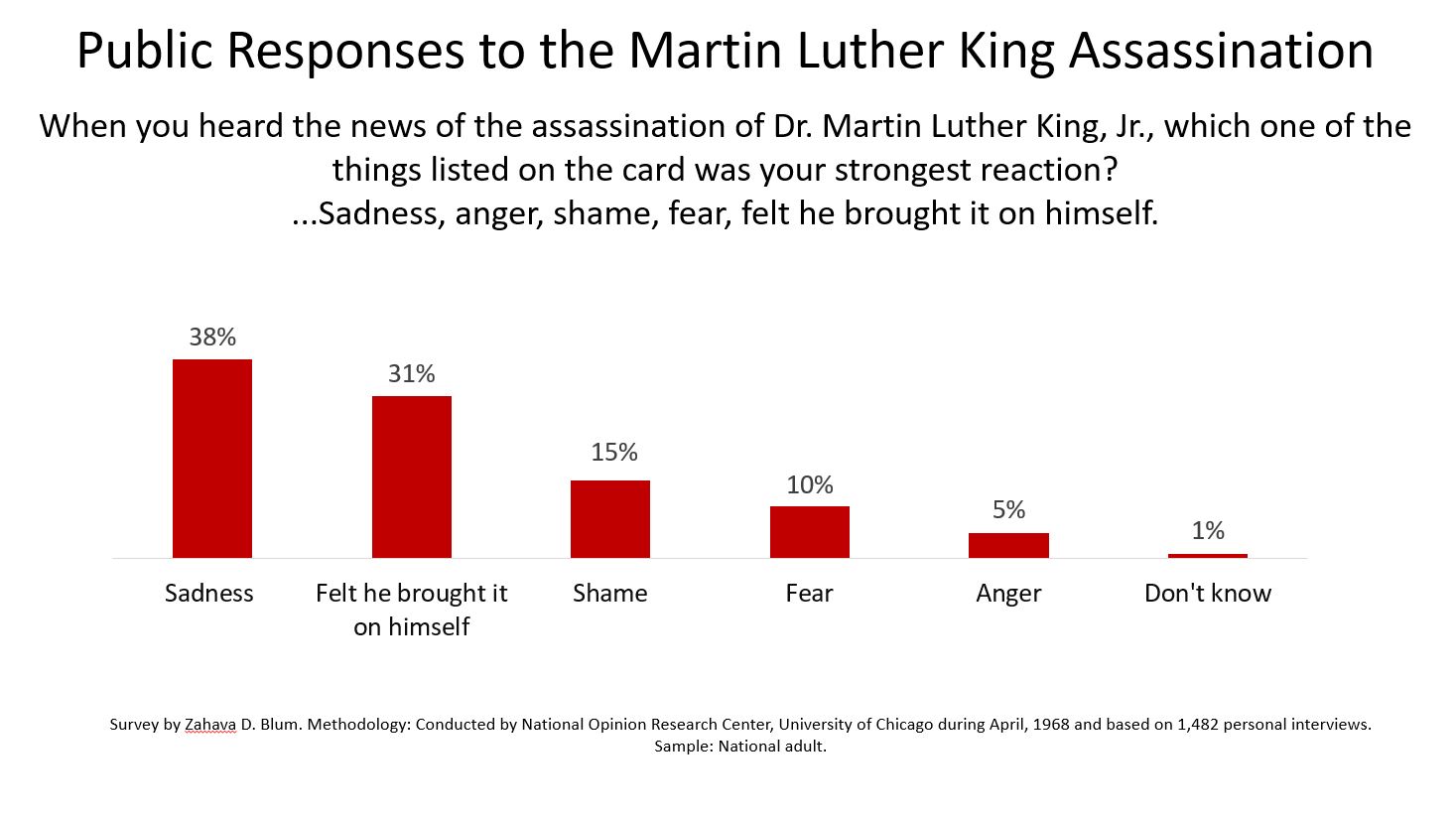

From a current viewpoint, there was surprisingly little polling conducted in the immediate aftermath of the King assassination about reactions to the murder itself or perception of possible effects on the civil rights movement. After President John F. Kennedy’s death in 1963, a large NORC survey explored public’s emotional reactions, perceptions of blame, attention to news coverage, and expectations about what would happen to Jack Ruby. No such poll was taken after King’s death. A number of questions were asked about handling the riots that followed King’s murder, but only one major national poll asked about reactions to the assassination itself. In this poll, a plurality said they had felt sadness, but nearly a third thought King had brought it on himself.

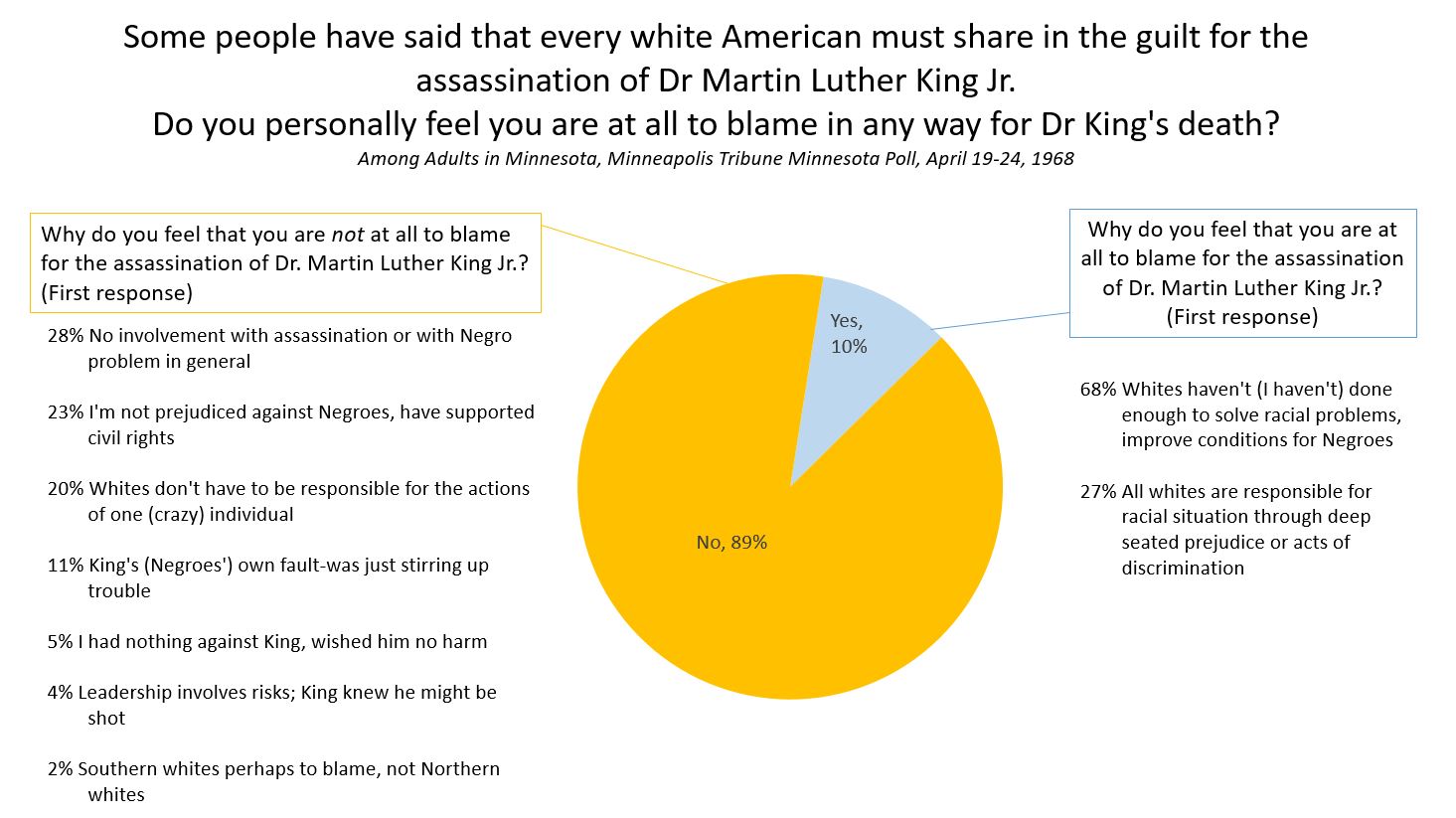

A Minnesota state poll conducted in April 1968 did ask about whites’ personal sense of blame for the assassination. Only 10% of whites felt they bore any blame for what had happened to King. The majority of those who did feel they were at all to blame said they didn’t do enough to solve racial problems, while 27% said all whites held prejudice. Those who felt they were not to blame gave a broader range of responses, but a plurality simply said they were in no way involved. The same poll did find that a strong majority of Minnesotans believed that “most white people in the United States have racial prejudice” (42%) or some do (44%).

A Minnesota state poll conducted in April 1968 did ask about whites’ personal sense of blame for the assassination. Only 10% of whites felt they bore any blame for what had happened to King. The majority of those who did feel they were at all to blame said they didn’t do enough to solve racial problems, while 27% said all whites held prejudice. Those who felt they were not to blame gave a broader range of responses, but a plurality simply said they were in no way involved. The same poll did find that a strong majority of Minnesotans believed that “most white people in the United States have racial prejudice” (42%) or some do (44%).

The minimal polling response to the assassination reflects a lower level of public opinion research on King than other major figures. Before his death, the most recent question on King’s role in the civil rights movement had come in December 1966, when Louis Harris found 50% of white Americans believed King was “hurting the Negro cause of civil rights”, with just 36% saying he was helping. The last question of any kind to be asked about King before April 1968 was a hypothetical matchup of four possible Presidential candidates conducted by Gallup in May 1967. King drew 2% support. Political figures who were generally expected to run for president, like Eugene McCarthy, Nelson Rockefeller, Richard Nixon, and George Wallace, were mentioned in polls with much greater frequency in early 1968 than the civil rights leader.

Has anybody here seen my old friend Bobby

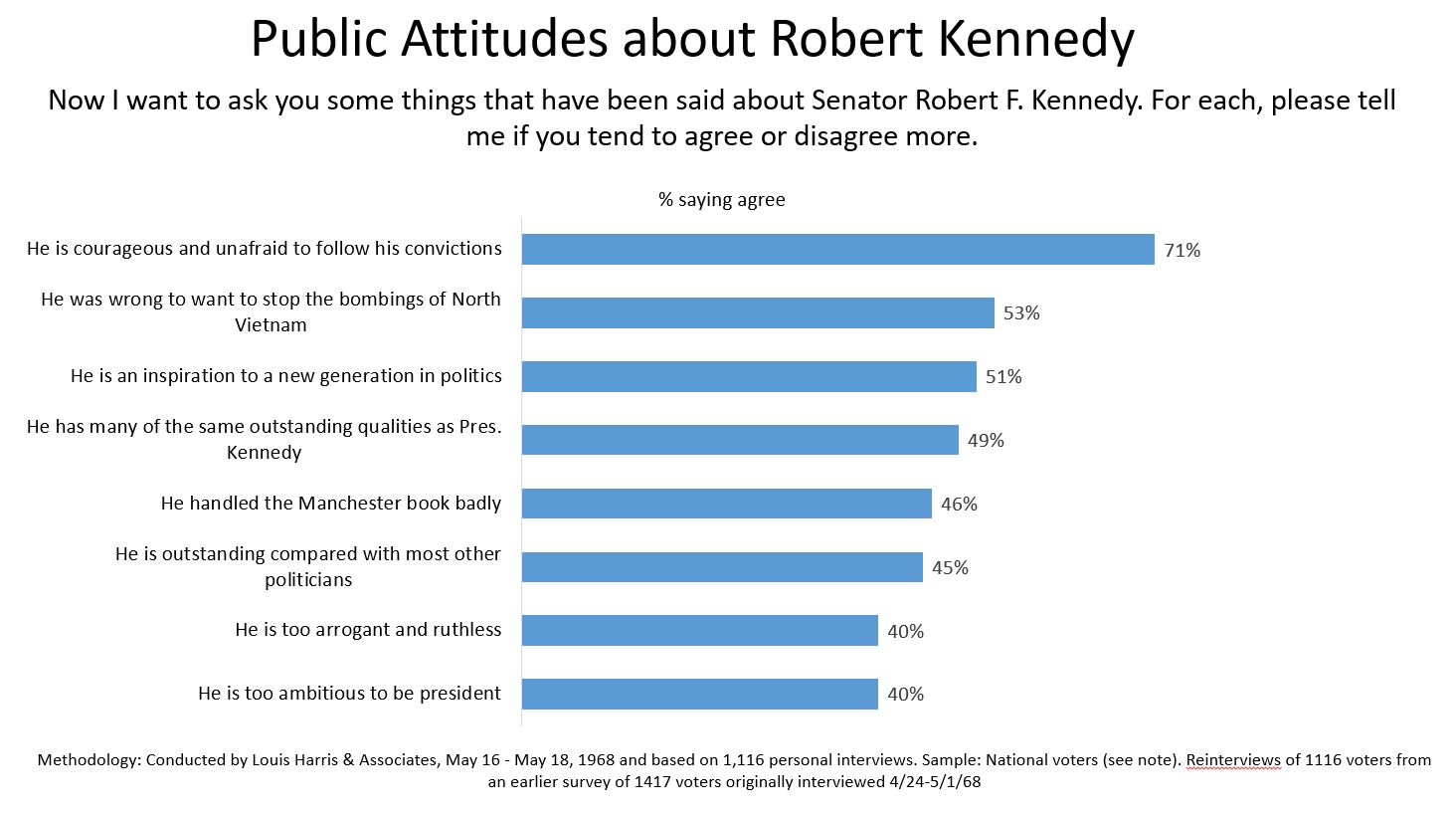

For this reason, the public perception of Democratic candidate Senator Robert Kennedy before his assassination was better documented than attitudes about King. Feelings about Kennedy were mixed. While a solid majority believed he had the courage of his convictions, just over half thought at least one of those convictions – opposition to the bombing of North Vietnam – was wrong. About half saw him as inspiring a new generation and sharing some of the outstanding qualities of his brother, but four in ten considered him ruthless and overly ambitious.

As a candidate, Kennedy had been polling evenly with Lyndon Johnson, 41% to 40%, in a February Gallup poll, an unusually strong showing against an incumbent of the same party. Johnson's weak position in the polls and his poor showing against Eugene McCarthy in the New Hampshire primary in March are often cited to explain why the President chose not run for re-election. Insiders from the Johnson administration, however, insisted that internal polling showed him winning handily and his decision was motivated by the problems in Vietnam.

As a candidate, Kennedy had been polling evenly with Lyndon Johnson, 41% to 40%, in a February Gallup poll, an unusually strong showing against an incumbent of the same party. Johnson's weak position in the polls and his poor showing against Eugene McCarthy in the New Hampshire primary in March are often cited to explain why the President chose not run for re-election. Insiders from the Johnson administration, however, insisted that internal polling showed him winning handily and his decision was motivated by the problems in Vietnam.

Whatever the explanation, Johnson's withdrawal from the race left Kennedy up against Senator Eugene McCarthy and Vice President Hubert Humphrey for the Democratic nomination. A May Gallup poll found Humphrey with a small lead against his opponents, pulling 34% support against 28% for Kennedy and 26% for McCarthy. But in hypothetical matchups against the likely Republican candidates, the picture was mixed. Kennedy was polling roughly at a level with the Republican forerunners in a May Gallup poll, drawing 35% against 37% for Nixon and 39% against 37% for Rockefeller. In comparison, Nixon beat Humphrey handily, 43% to 32%, but Humphrey beat Rockefeller, 41% to 34%. (George Wallace drew support in the mid-teens in all these matchups.) The country would never have the opportunity to see if Kennedy could defeat Nixon. With the nation still reeling from the assassination of King, on June 5th Robert Kennedy was shot on the campaign trail.

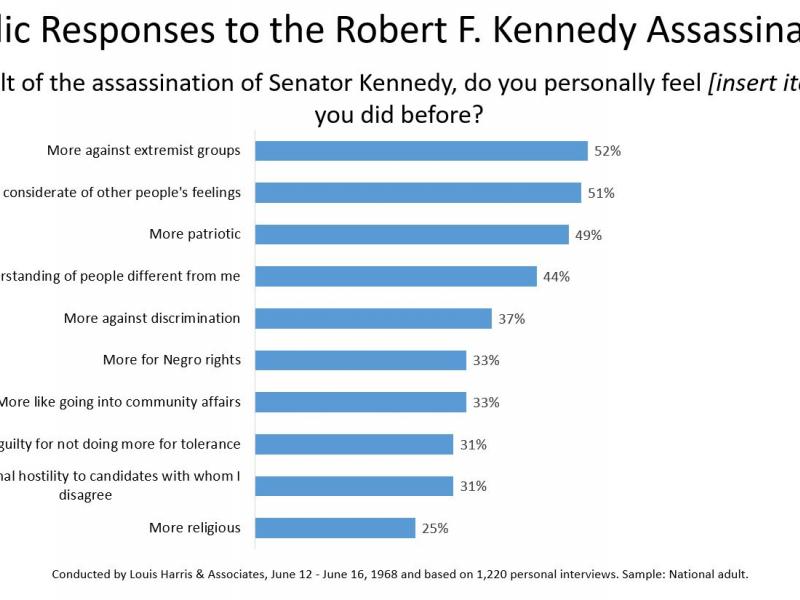

The following week Louis Harris polled responses to Kennedy's assassination. Despite the possible social desirability of saying that a public tragedy had resulted in personal growth, majorities did not report having experienced most of the potential effects described. While just over half said claimed they had become more against extremist groups and more considerate of others' feelings, lower numbers reported having become more likely to go into community affairs, more for civil rights, less personally hostile to candidates with whom they disagreed or more religious.

The violence against leaders in 1968 contributed to a general sense that the country was in disarray. Fifty-seven percent of Americans in the June Harris poll agreed that "our political process has fallen apart when candidates can't campaign without fear of assassination." Still, the murder of two major leaders didn't seem to affect the public's view of the biggest problem facing the country. When Gallup posed this question in July 1968, civil rights and demonstrations/riots had risen substantially from when this question had last been asked in February, but the top problem remained the same as it had been and could continue to be for some time: Vietnam.