In Vietnam, no one called 1967 the Summer of Love.

With half a million US troops on the ground and almost twice that number of allies, the year was to see the largest-scale battles in the conflict so far. Several massive efforts to destroy North Vietnamese forces in the area dubbed the “Iron Triangle” were tactical successes but did little to change the overall strategic picture of the war. While US commanders hoped to seize the initiative in the struggle with the various operations, events of the following year such as the Tet Offensive and the Battle of Khe Sanh would show that the enemy was far from on their heels. Despite typical reported casualty ratios of 10-1 in American favor, as the year wore on the rising casualties and lack of demonstrable victories began to erode the public’s support for both the war and the president.

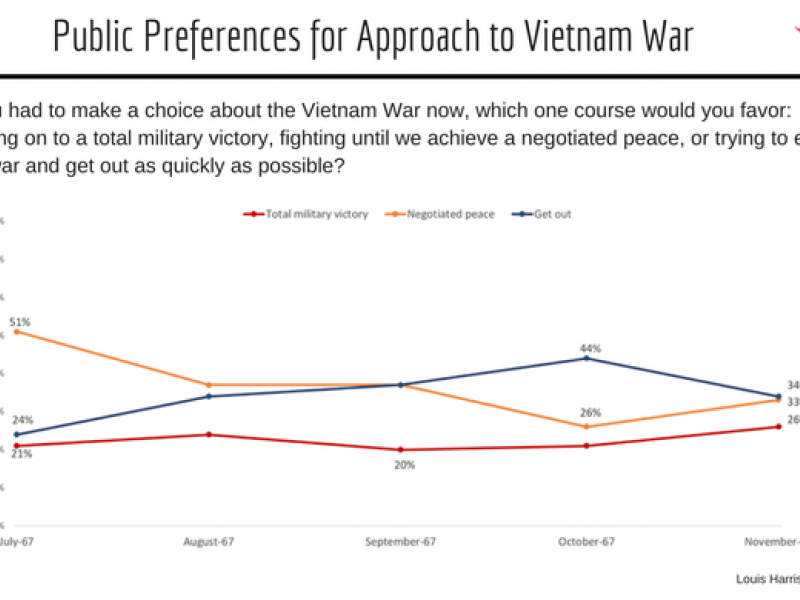

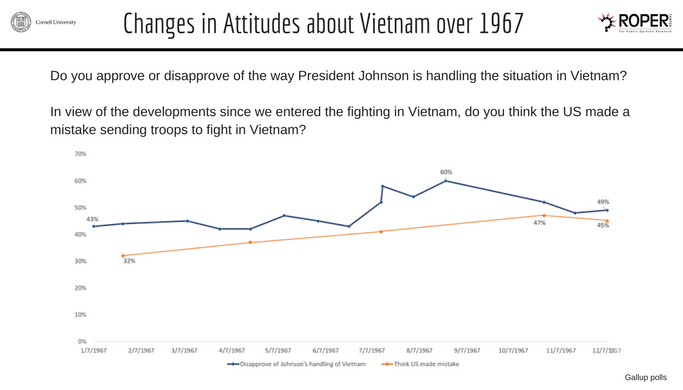

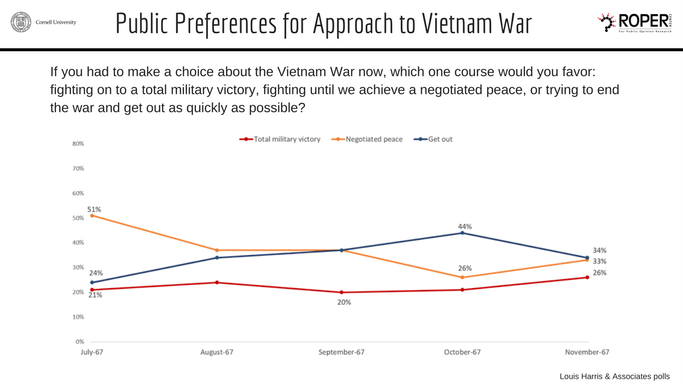

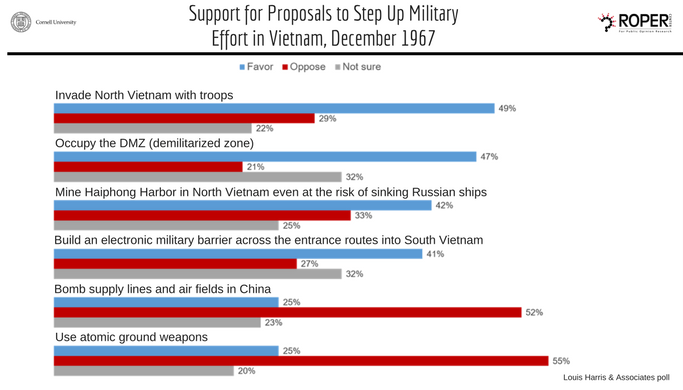

Disapproval of Johnson’s handling of the war went from 43% in January to a peak of 60% in late August, dropping back to 49% at year’s end. The view that the US had made a mistake in sending troops to Vietnam steadily increased from 32% to 45%. In the last half of the year the public preference for how the war should be conducted also began to shift. While the proportion calling for “total military victory” went up from 21% to 26%, and the 51% who wanted a “negotiated peace” fell to 33%, those who simply wanted the US to “get out as quickly as possible” went from 24% to a peak of 44% before ending the year at 34%. By December, pluralities supported more militant options such as invading North Vietnam itself, occupying the DMZ, and mining Haiphong harbor, but majorities opposed major escalations such as attacking supply lines and airfields in China and introducing nuclear weapons. In December 1966, only 15% of Americans had thought the war would be over by the end of 1967. That pessimism proved prophetic.

Protests against involvement in the war began to increase in size and frequency during 1967, culminating in 100,000 people gathering in Washington DC in October. Demonstrations were also ramping up on college campuses across the nation. Polling in 1967 itself rarely addressed these protests, though the exception indicated approval was likely low. In a December Harris poll, 40% of Americans didn’t think people who were against the war in Vietnam even had the right to undertake peaceful demonstrations against the war. The next year, as protests continued, polls addressed the issue more frequently. An April NORCE poll found 60% thought that college protests were not a healthy sign for America. More dramatically, 56% in a 1968 Gallup poll approved of Chicago police beating anti-war protestors at the Democratic National Convention that summer. While this discontent would soon lead to President Johnson’s stunning decision not to run for re-election in 1968, polling clearly indicates how deeply divided the nation was on the subject of Vietnam and makes Nixon’s victory amid promises to swiftly end the conflict unsurprising.

Carl Brown is iPoll Acquisitions Manager. He has been with the Roper Center since 1999, and currently collects and prepares new polls for entry into the iPoll system and selects poll questions for our daily Twitter feed. He has a B.A. in Modern European History and an M.A. in American History from the University of Connecticut.