By Hyein Yang

1. Introduction

During COVID-19 pandemic, countries and individuals around the world encountered a profound economic downturn. In response, numerous governments implemented diverse policies aimed at extending economic support and alleviating the burdens faced by workers and families, and President Biden also announced his plan to invest and provide relief funds.

Some people compared the pandemic situation with the Great Depression. In the 1930s, the US experienced a substantial economic hardship as disruptive as COVID-19. American citizens underwent the widespread job and home losses as a result of the persistent economic downturns. Moreover, as severe drought persisted during the 1930s in Midwest and southern Great Plains areas, rural Americans suffered severe losses. These circumstances left workers and families grappling with the challenge of survival, which was not possible without the federal government’s support.

To help American citizens, President Roosevelt provided federal relief by creating New Deal agencies and providing economic aid for the citizens. Congress also passed legislation aimed at providing economic support to citizens, a course of action initiated by President Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s actions raise a question: Did individuals who received economic support from the federal government exhibit a greater likelihood of supporting the president? Existing studies have examined how economic status of voters affects national election outcomes and political participation (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2000; Fiorina, 1981; Nadeau and Lewis-Beck, 2001). While debates persist regarding the causal relationship, numerous studies demonstrate that the provision of economic support and crisis management by the federal government, especially after experiencing natural disasters or economic hardship, can have a positive effect on approval ratings for the political leaders (Margalit, 2019; Achen and Bartels, 2004; Gasper and Reeves, 2011; Bechtel and Mannino, 2022). Furthermore, scholars have also explored the strategic allocation of federal relief and grants, examining how these choices could impact voters’ decision to punish or reward incumbent presidents (Kriner and Reeves, 2012; Cox, 2009).

However, public opinion regarding the president after receiving federal funds during the 1930s remains unexplored. This gap is primarily because of the lack of high quality public opinion datasets and limited surveys conducted during that era. Using public opinion data from the Roper Center, however, it becomes possible to access data from the 1930s and examine how American citizens assessed federal relief programs, as well as and how these programs shaped public’s views on the president. This analysis could shed light on the dynamics between government assistance, public opinion, and its impacts on political support for the leaders.

2. Public Opinion Data in the 1930s

Public opinion polling data has been considered a great asset for presidents, providing insight into public perceptions of their job performance and support for their policies. According to Herbst (2021), professional pollsters started emerging in the Great Depression era, making public opinion surveys a significant resource (Herbst, 2021). The importance of understanding public opinion became especially pertinent due to the expanding role of the federal government in the 1930s and 1940s, .

The Gallup Poll is one of the oldest major professional pollsters in the US. In 1935, the Gallup Poll published its first public opinion data. The Roper Center has the Gallup data collection, encompassing public opinion datasets dating back to 1936, which enables the study and tracking of public opinion even during the 1930s. Notably, Gallup asked questions regarding the federal government and its relief programs, providing a valuable dataset for exploring the role of public in offering feedback on federal policies and regulations.

While modern surveys employ probability sampling to generate estimates that are representative of the entire population, early polls prior to the 1950s relied on quota-sampling methods. These methods, disproportionally based on quotas for specific groups of people as targeted respondents, led to skewed samples and introduced distortions in analyses (Berinsky et al., 2011). To address this issue, Berinsky and Schickler employed cell weighting and ranking methods. Using public opinion data from the Roper Center’s Berinsky and Schickler American Mass Public Study collection, this post examines the relationship between the distribution of federal relief and public support for the president in 1937. By using improved representation of public opinion with minimized bias, this post aims to shed light on the correlation between economic assistance by the government and public sentiment toward presidential leadership during that era.

3. Data Analysis and Results

This post seeks to examine the relationship between federal relief distribution and public approval of the president and electoral preferences. To understand this connection, I will analyze the December 1937 Gallup Poll data. This survey asked questions about the experience of receiving economic assistance from the federal government and respondents’ perception and stance towards the president.

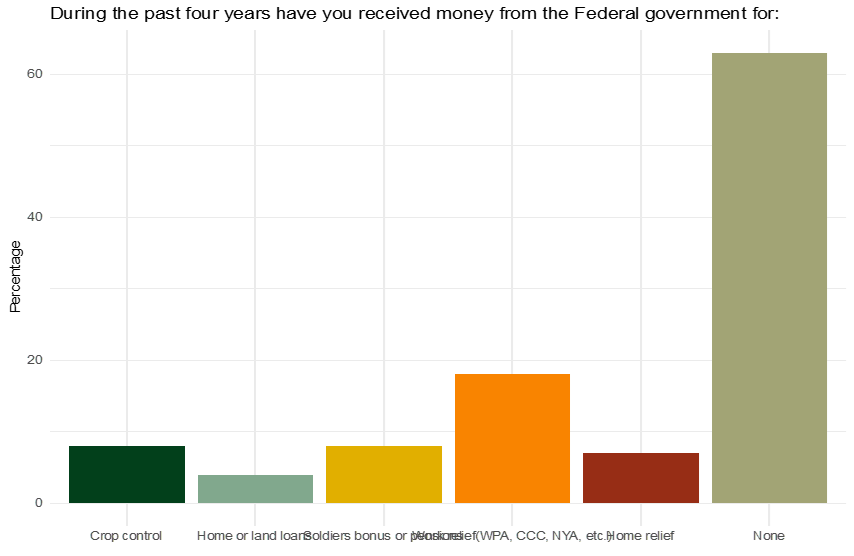

One of the questions in this survey was about whether individual respondents had received financial support from the federal government over the preceding four years for various purposes, such as crop control, soldiers’ bonus or pensions, home or land loans, home relief, or work relief. Surprisingly, more than 60% of the respondents said they had not received any federal relief to alleviate their economic burdens (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Economic Support by the Federal Government

In terms of support for the president, questions asking respondents for their opinion about the president can allow useful analysis. First, one question probed whether respondents favored President Roosevelt’s third term or not, serving as a valuable way to measure support for Roosevelt. Additionally, using two questions regarding respondents’ electoral preferences for each candidate can offer an alternative approach to measuring the public’s support for the president. Specifically, these questions inquired about the candidate respondents had supported in the previous election and whether they intended to vote for the same candidate again. For those who previously voted for President Roosevelt and would vote for him again, we can consider they expressed their intention to support him; conversely, those who altered their decision to vote for another candidate can be considered as not supporting the incumbent president.

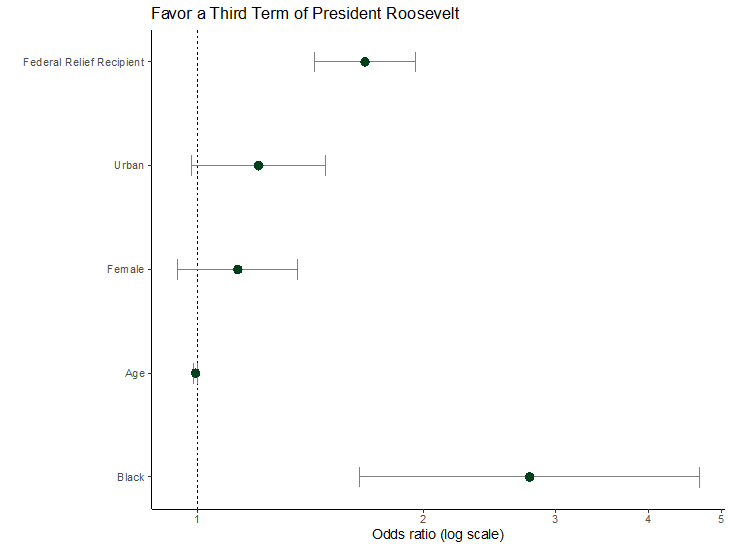

Figure 2 Logistic regression result about individuals’ reception of economic support from the federal government and its influence on their support for President Roosevelt’s third term.

To understand the correlation between receiving federal relief and support for the president, this analysis employs logistic regression, a method for analyzing binary variables as dependent variables. Illustrated in Figure 2 and 3 are the results in terms of odd ratios, indicating the likelihood of an outcome occurring. Consequently, individuals who received federal relief were approximately 1.7 times more likely to support the president than respondents who did not receive federal relief. Furthermore, with each additional federal relief program, respondents’ odds of supporting the president increased by a factor of 1.7.

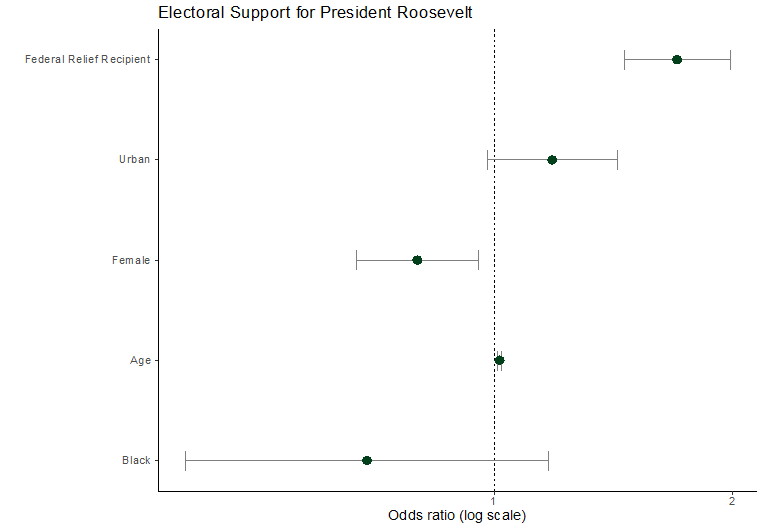

Figure 3 Logistic regression result about individuals’ reception of economic support from the federal government and its influence on their voting decision to reward President Roosevelt.

Respondents’ support for the president using different measurement provides a similar result. As demonstrated in Figure 3, for every extra federal relief program received, respondents exhibited about a 1.7x increase in the likelihood of supporting President Roosevelt in a presidential election. Electoral support in this analysis includes respondents who both voted for President Roosevelt and expressed their intention to do so again, as well as those who originally voted for other candidates but indicated they would vote for President Roosevelt in the next election.

These findings align with prior research suggesting that the distribution of federal grants could increase public support for the president. While there was no presidential approval question directly asked and therefore we could not control for the possible impacts of partisanship of each respondent, it is still valuable that the Gallup poll included questions about the receipt of various federal relief programs and sentiments toward President Roosevelt’s potential next term, as well as voting decisions.

4. Conclusion

Using public opinion data in the 1930s presents both challenges and rewards. However, it is crucial to comprehend historical public opinion, especially considering the heightened significance of understanding public opinion due to the expanded role of the federal government since that time. While the number of direct inquiries about individuals’ receipt of economic support from the federal government is limited, this public opinion dataset from the 1930s offers a valuable chance to investigate how American citizens, during economic crisis, perceived the distribution of federal relief and how it influenced their evaluation of the president’s performance.

Spanning from the Great Depression in the 1930s and the most recent COVID-19 pandemic, there have been several economic recessions in American history, which necessitated federal government support. Using the Berinsky and Schickeler datasets collection available through the Roper Center, follow-up studies could investigate and compare public opinion on the federal relief and support for the president over time, while accounting for appropriate weighting methodologies to ensure comparability across different time periods.

References

Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2004). Blind retrospection: Electoral responses to drought, flu, and shark attacks.

Bechtel, M. M., & Mannino, M. (2022). Retrospection, fairness, and economic shocks: how do voters judge policy responses to natural disasters?. Political Science Research and Methods, 10(2), 260-278.

Cox, G. W. (2009). 13 Swing voters, core voters, and distributive politics. Political representation, 342.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective voting in American national elections. Yale University Press.

Gasper, J. T., & Reeves, A. (2011). Make it rain? Retrospection and the attentive electorate in the context of natural disasters. American journal of political science, 55(2), 340-355.

Kriner, D. L., & Reeves, A. (2012). The influence of federal spending on presidential elections. American Political Science Review, 106(2), 348-366.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2000). Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annual review of political science, 3(1), 183-219.

Margalit, Y. (2019). Political responses to economic shocks. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 277-295.

Nadeau, R., & Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2001). National economic voting in US presidential elections. The Journal of Politics, 63(1), 159-181.

Hyein Yang is a Ph.D. student in the Government Department at Cornell. Her research interests include the American presidency, federalism, the checks and balances system, and public opinion. Her current research projects explore how state-level political actors—state attorneys general and governors—can play a pivotal role in constraining presidential power within the vertical system of checks and balances. Her Kohut Fellowship project will examine how the federal government's economic assistance after the disasters affects public attitudes toward the president and the expansion of the federal government. In particular, this project investigates federal emergency relief in the aftermath of the Dust Bowl in the 1930s and its impact on public attitudes and participation.