The meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi revitalized the public debate over the value and safety of nuclear energy. Do Americans see a nuclear plant as a devastating accident waiting to happen - or the solution to climate change?

Early polling on nuclear energy

Americans believed in the potential for nuclear power from the first years after WWII. Forty-eight percent of the country in a 1945 NORC poll said they expected atomic power to be put to general everyday use by industry with ten years; 22% thought between 11 and 50 years, 26% just didn't know. Concerns about atomic power were focused on nuclear war, not waste or accidents, and these concerns were limited. In a 1957 Roper survey, 20% believed that nuclear power was almost sure to bring great benefits to mankind, 56% thought it could help us if we learn to use it wisely, and only 14% were doubtful that it would be used wisely or certain it would not be. A few years after Shippingport Atomic Power Station, the country's first nuclear power plant, was opened in 1958, the country's positivity was slightly more reserved. In a 1964 Institute for International Social Research/Gallup poll, nearly half the country (45%) believed that the development of nuclear power would turn out to be a benefit to mankind, but 28% thought it would be a curse, 14% said both or neither, and 13% didn't know. Still, the country had fairly positive views about nuclear power into the 1970s. In a 1976 Cambridge Reports/Research International poll, about half the country (48%) favored the construction of more nuclear power plants, while 31% opposed.

Three Mile Island

On March 28, 1979, a partial nuclear meltdown at the Three Mile Island reactor in Pennsylvania led to the evacuation of area residents and a renewed national debate about the safety of nuclear power. In the wake of the disaster, the public was split in their response to the event. While 42% in a Cambridge Reports/Research International poll said the accident made them less inclined to support the development of nuclear power as an energy source, an equal proportion said it did not affect their opinion. The public was more united in opposition to the idea of closing nuclear power plants in response. Only 23% said that all plants should be closed, 60% disagreed. This response was perhaps unsurprising in a year when, in poll after poll, the public named the energy crisis and fuel shortages second only to inflation/cost of living as the most important problem facing the country.

Chernobyl

Seven years later, failures at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine resulted in the worst nuclear accident in history. For the first time, a majority (62%) opposed the building of more nuclear power plants in the U.S., a shift in public support that proved long-lasting. Although most did not want more nuclear power plants, a majority did not go so far as to advocate shutting down the currently operating plants. In a Gordon Black/USA Today poll in April, 1986, those who oppose building more plants were asked if U.S. nuclear power plants should continue to operate; 47% said they should, while 45% said they should be shut down. A Cambridge Reports/USCEA poll taken in November of that year captured the uneasy relationship Americans had with nuclear power at the time. When asked to think about all energy sources available for large-scale use, about half the country (52%) described nuclear as a "not good, but realistic choice." The rest were split evenly between those who thought it was a good choice (23%) or a bad one (23%).

A growing acceptance of nuclear power

By the early nineties, strong majorities also supported the use of nuclear energy as one of the ways to provide electricity in the United States. Though levels have varied substantially, support on this measure has been higher than opposition over the last decade. Opposition to building new nuclear power plants also decreased. Questions in the 2000s found the country either fairly evenly split or strongly supportive, depending on question wording and year, with peak support at 70% in a 2010 poll.

Fukushima Daiichi

In March 2011, a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi plant in Japan, triggered by the tsunami that hit the country, became the second-worst nuclear disaster in history. Thirty-eight percent in a Quinnipiac poll said the accident made them less likely to support the construction of new nuclear power plants in the U.S., 57% said it had no effect. Although support for the use of nuclear energy as a way to provide electricity in the U.S. did drop by September of 2011, those favoring nonetheless nearly doubled those opposed. Interestingly, a 2015 poll, four years after the disaster, shows the lowest levels of support in a decade.

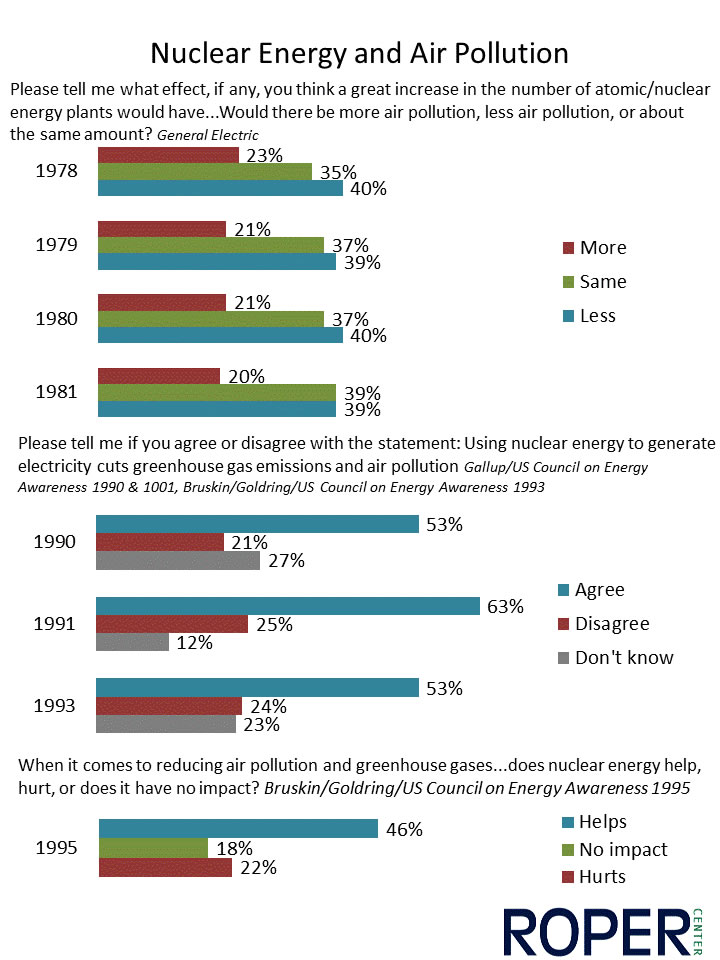

Nuclear power and global warming

While the history of support and opposition to nuclear power has been largely defined by the series of accidents that have brought safety into question, nuclear energy's role in preventing air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions has also been important in decision-making around nuclear energy development. Nuclear energy supporters have long extolled the beneficial effects of replacing high-emissions energy sources like coal, but the public was not easily convinced. Large segments of the public in the late seventies and early eighties did not believe that nuclear power provided such benefits. By the nineties, slim majorities agreed that nuclear cut greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. About a quarter disagreed, and the substantial remainder didn't know.

Polls over the last decade have shown that most people do not make strong associations between nuclear energy and climate change solutions. Furthermore, 44% believe that nuclear plants contribute "a lot" or "some" to global warming. If the public came to associate nuclear energy strongly with preventing global warming, support for nuclear would likely increase - at least, unless another accident brought another shift in public opinion.