Large sample surveys of the general population in countries across West Africa before the advent of the Afrobarometer are difficult to come by. Much of the social science research concerning the ideas, preferences, attitudes, and political behavior of individuals in the years surrounding independence (the 1960s for many countries on the continent) either relied on thick but narrow studies of specific communities or was gleaned broadly from more accessible elites – such as officials in state bureaucracies, expatriates living in Europe, and high ranking politicians.

As a student of national identity formation and African politics, this left me wondering about the opinions of the individuals I might pass by on the street – were I walking the neighborhoods of Dakar in the 1960s, that is. What did they think of the new era of politics and society that was introduced at the dawn of independence?

To my pleasant surprise, the Roper Center retains a survey conducted from 1961-1962 across five countries in West Africa among its broader collection of studies from the era and the region. Of particular interest, this survey asked individuals about their thoughts on a politically unified Africa – and who they thought was best suited to lead that entity. I explore this survey below after a quick detour explaining why the timing of this survey fascinates me.

Critical Junctures in History

The roots of national consciousness push deeper back in time, but the postwar period through to the dawn of independence was a critical era of identity formation in many places across Africa (late-1940s through the 1960s). Figures such as Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana rose to prominence in the 1940s and 1950s, influencing both the trajectory of independence for African states as well as the national identities that would emerge alongside statehood in the 1950s and 1960s.

By this same period, theorization of Pan-Africanism too had a deep, rich, and multi-faceted history. Conceptualized in various ways – including ideals, values, institutions, continental politics, international relations, and economic integration – 20th century Pan-Africanism was a topic of discussion within circles populated by thought leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and George Padmore.

Securing independence is what might be called a critical juncture. These were moments of great change, where newly available policy options and political alliances offered great potential for new directions. Within these opportunities were contending ideas of nationalism and supranationalism. Many individuals across newly independent states were offered the opportunity to endorse nationalist platforms at the ballot boxes and subsequent survey research has demonstrated an increasing attachment to national identity across Africa (e.g. Robinson 2014). However, while we might sketch the rough contours of nationalism across general populations, a sketch that changes and accrues greater detail with each public opinion survey, questions of popular support for Pan-Africanism at the dawn of independence are difficult to answer.

New Old Data: The Five Country Study

Locating survey data concerning public opinion in West Africa prior to the age of the Afrobarometer is a difficult task. However, among a number of fascinating surveys querying general publics throughout Africa on topics as diverse as their media consumption habits, hopes for their families, and opinions of Western countries, the Roper Center has available intriguing survey data on attitudes towards pressing questions of the early independence era.

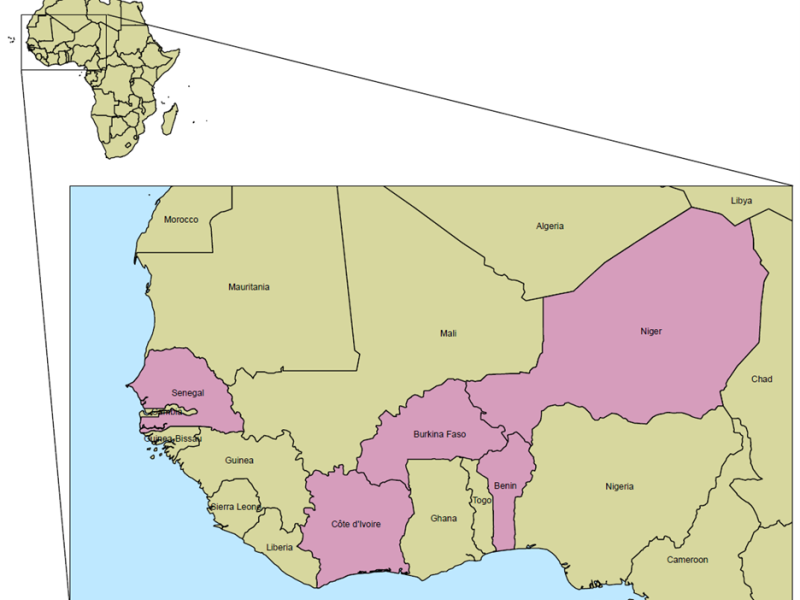

From 1961-1962, the French National Centre for Scientific Research conducted a survey of five countries in West Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Niger, and Senegal. Each country secured its independence shortly before the survey was fielded and each was wrestling with questions of policy direction and national identity. Sampling 15 to 30-year-olds from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds across rural and urban communities, this survey gives us a glimpse into the thoughts and opinions of West Africans on the ideal roles of traditional authorities, gender and politics, impressions of European countries, and even Pan-Africanism. While each of these would easily serve as the basis for a captivating study, I chose to explore the question of support for Pan-Africanism among the general public.

Trends in the Data

It is worth noting right away that most of the individuals surveyed supported the unification of Africa. The question wording presupposes a concrete political conception of unification. Item #8A of the questionnaire reads: “Do you wish personally that all the African countries join together in order to form a whole, a single unity?” More than 70% of respondents from each country affirmed their support for a unified African polity.

For those who support the idea, #8B asks them “Who seems fit in your eyes to be the leader of that unity?” The diversity in attitudes provides a stark contrast with the relative uniformity of general support. This is most apparent when considering the combined responses of those who think that it should be either their president or their country more generally that should lead the union.

Note: Bars report the percentages of respondents within each country from the subsample already supporting unification. Not present in the visualization are responses of a different country or president from one’s own leading the union. These responses were relatively rare. [JPS1]

Individuals from Côte d’Ivoire enthusiastically supported the idea of their country, if not President Houphouët-Boigny himself, leading a unified Africa. Conversely, respondents in Burkina Faso more commonly proposed alternative forms of governance, such as local representatives, the military, or religious communities (46%) than their own country or president as leader (16%). While this variation already suggests interesting points of entry for deeper analysis, the Roper data gives us the rare opportunity to explore trends across individual attributes among an under-surveyed population.

While most were likely to support a unified Africa, which group was more likely than others to respond positively to the survey prompt? The answer: women. Below is a plot of the average marginal effects of several independent variables on support for a politically unified Africa.

95% confidence intervals displayed in the plot

Women are just over 3% more likely relative to their male analogues to support a unified Africa. While this may seem small, this is among a population that already strongly supports a politically unified continent, so that this finding is statistically significant demonstrates the critical influence of gender on national and regional political attitudes

The association between gender identity and support for African unity is stronger than the latter’s association with moving up one level in education (for instance, from no schooling to primary, or primary to secondary schooling). However, there are five levels of education captured by the survey, so the overall change in the relationship for an individual with post-secondary education relative to their analogue with no formal education is roughly 12%.

Conclusion

This is but the tip of the iceberg. The five-country study probed opinions of the role of traditional leaders in a new era, the place of women and men in politics and society, opinions of European countries along with the US and Soviet Union, and much more. This initial cut analysis revealed broad support for a politically unified African continent with very different ideas of who should lead such an entity. The trends uncovered when drilling down to individual characteristics were no less fascinating, with gender playing a significant role in support for African unity.

By Joseph Lasky

Roper Center Kohut Fellow

12/4/2022