The Summer of Love was not the only nickname given to those months in 1967 when the world seemed to be changing at a record pace. Over 150 riots fueled by racial tensions erupted in American cities, an escalation of the outbreaks that had occurred over the previous years, giving rise to the moniker “The Long Hot Summer.” The public response to these events, as recorded in public polling from the period, underscored the racial divisions in the country.

Lighting the Spark

The first questions to address the causes of urban rioting in this period came in an August 1965 Harris poll, which asked respondents in their own words to name the two or three main reasons the riots broke out in “Negro areas” of Los Angeles, Chicago, and other places. No single answer dominated the responses, but the top reasons given were young punks and hoodlums on the loose (22%), unemployment and poverty (16%), and Communists (15%), while small percentages blamed hopelessness, harsh treatment by police, rabblerousers, and even hot weather.

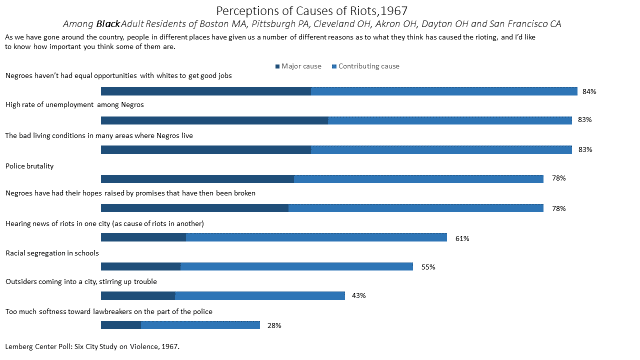

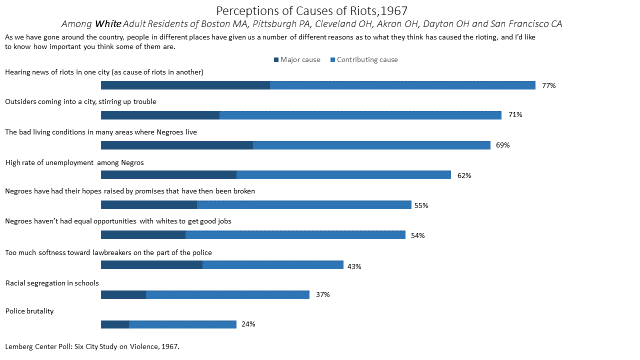

In the fall of 1966 and into March 1967, the newly created Lemberg Center for the Study of Violence at Brandeis University delved deeper into the roots of violent outbreaks in cities with a survey of residents in six northern U.S. cities. The study found stark differences between whites and blacks in perceptions of the causes of riots. Whites were more likely than blacks to see outsiders stirring up trouble or hearing news of riots in other cities as a cause of rioting. Blacks were more likely to blame riots on lack of opportunities, unemployment, bad living conditions, and racial segregation in schools. Nowhere did black and white views diverge more dramatically than on police brutality. Perception of police brutality as a cause of riots was 54 percentage points higher among blacks than among whites.

In July 1967, Lyndon Johnson appointed the Kerner Commission to determine what was causing the rioting and how to prevent more unrest in the future. But the findings of the Commission, released in February 1968, did not unite Americans in a shared understanding of what was happening in U.S. cities. In a March 1968 Harris poll reported in the Washington Post, 37% of Americans agreed with the Commission’s view that the 1967 race riots were brought on mainly by white racism; 49% disagreed. A majority of whites (53%) rejected this idea, with just 35% agreeing. In contrast, 58% of blacks supported it, and only 17% disagreed. Again, particularly sharp divisions were found on the role of police brutality in the riots; 51% of blacks, but only 10% of whites, believed this was a major cause.

Ball of Confusion around Solutions

Given the lack of consensus on the causes of riots, it’s unsurprising that the public did not agree on solutions. A 1966 Harris poll found the country rather pessimistic about the effect of the antipoverty bill on outbreaks of violence. Just over a third (35%) though the bill would get at the causes of racial unrest, 45% said it would not. As with many other questions about the causes and solutions to racial problems in the country, there was a substantial proportion (20%) who said they didn’t know.

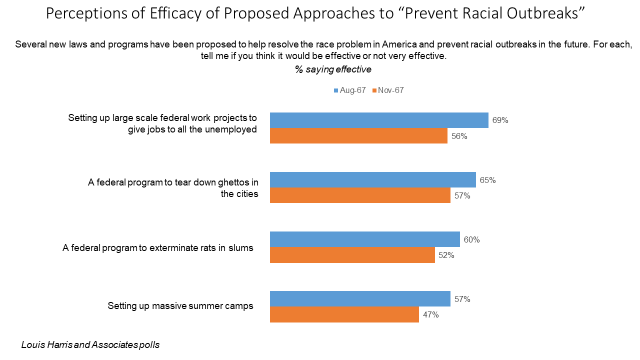

Harris polls in August and November of 1967 showed that majorities thought that a number of approaches could be effective in preventing “racial outbreaks,” from federal works projects to exterminating rats in the “slums.” The results in November showed a small, but consistent, decreased optimism from August.

One idea that was circulating at the time was that perhaps the cities themselves were to blame for the problems, and that encouraging black people to move out of large Northern cities into smaller towns or cities would decrease outbreaks of violence. In a 1966 Gallup poll, the country was divided on this notion: 34% thought it would be a good idea, 39% a poor idea, and 26% had no opinion.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968, riots again broke out in cities around the country. Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago issued an order to “shoot to kill arsonists” and “shoot to maim looters.” A May 1968 Gallup poll asked respondents their feelings about this order to “shoot on sight anyone found looting stores during race riots.” More than half (54%) said that this was indeed the best way to deal with this problem, while 41% thought there was a better way.

The View from the States

Several state polls also addressed questions about urban rioting. Unfortunately, smaller sample sizes and sometimes a lack of demographic questions limit the value of historical data at the state level by preventing analysis of responses by race. But the overall results from 1967 polls in Minnesota and Iowa reflect attitudes seen in national polls at the time.

Minneapolis had experienced an episode of looting and arson on Plymouth Avenue in 1966. In June of 1967, before a major Minneapolis riot in July, the Minnesota Poll asked Minnesota residents whether the recent outbreaks of rioting were a result of racial discrimination or outbreaks by hoodlums and lawless elements. Thirty-two percent said discrimination; 49% said hoodlums.

Minnesotans were also split on the best response to riots. When given a list of options, a plurality of 29% said city policy should take a firmer hand before riots could break out, and 18% thought the “Negro community should restrain its own people.” But 24% thought white middle class Americans should do more to “help and understand the Negro,” and 16% thought the federal government should do more to eliminate poverty.

The poll found Minnesotans had mixed views about the relationship between the riots and the Civil Rights Movement. When asked if there were a connection between the two, 49% said there was, 38% disagreed. A full 65% thought the riots were planned, rather than just flare-ups that got out of control.

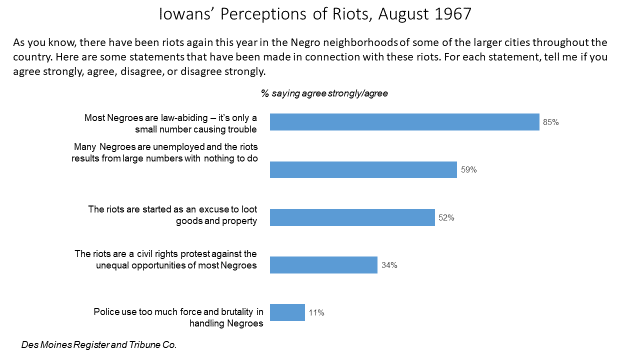

Incidents in Waterloo and Des Moines, Iowa in early summer led to questions about rioting in a Des Moines Register and Tribune Co. Poll in August 1967, and Iowans expressed mixed attitudes. Respondents to this poll were overwhelmingly white, reflecting the demographics of Iowa as a whole, and their attitudes were in line with whites in the Lemberg survey. Strong majorities agreed that the riots were the result of a small number of troublemakers, not the majority of “law-abiding” black Americans. Most did not see the riots as a civil rights protest; a larger proportion saw them simply as an excuse to loot. Nearly all respondents rejected the idea that police had treated black citizens with brutality.

Kathleen Weldon is Director of Data Operations and Communications at the Roper Center. She manages data provider relations, oversees the data curation process, plans archival development, and works closely with the IT development team in building new user tools.