By Samuel Liu (PhD Candidate, Department of Government)[1]

The July 1, 1997 sovereignty transfer of Hong Kong from the U.K. to China transformed the last major British colony into a Special Administrative Region of China. The result of a decade of Sino-British negotiations mandated that Hong Kong’s sovereignty be returned to Beijing on the principle of “One Country, Two Systems”, designed to ensure Hong Kong’s continued economic and political distance from the mainland. While the fresh memory of the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989 cast doubts on Beijing’s commitment to the institutions that would guarantee Hong Kong’s autonomy, the 1997 handover proceeded largely unopposed.

Today, many Hong Kongers feel that the commitment fell flat. Large-scale protests in 2014 and 2019-2020 failed to achieve the democratic reforms sought by Hong Kong’s pro-democracy camp. In response, Beijing imposed sweeping changes to Hong Kong’s political landscape, granting itself broad powers to suppress protests, jail critics, and control local elections. While the fundamentals of Hong Kong’s economy–its simple and low-rate tax regime and currency stability–remain sound, the perception of political intervention has lowered investor confidence and driven out capital.

Hong Kong’s autocratization over time raises important questions about public opinion in 1997. Facing a potential seismic shift in their way of life and economic conditions, how prevalent was people’s support for returning to China? What factors contributed to Hong Kongers’ preference for returning to China, as opposed to alternative pathways like remaining a colony or seeking independence?

Tracking Public Opinion on the Handover

To answer these questions, researchers and news agencies in Hong Kong stepped up efforts to collect public opinion data from the 1980s onwards.

The Hong Kong Transition Project (HKTP) represented the most systematic academic effort to track public opinion at the time. HKTP tracked Hong Kong’s preference for Chinese rule over other pathways bi-annually from 1993 to 1997, and remained operational as a think tank after 1997.

The Public Opinion Programme (POP) at the University of Hong Kong began in 1991, and its successor PORI still operates in Hong Kong today. An estimated 120 polls were commissioned by media outlets in just 1992-1993, including both academic polling resources and private consultancy services.[2] The South China Morning Post’s chief pollster, Asian Commercial Research (ACR), conducted polls on preferences about the handover on more than 10,000 respondents over a decade.[3]

Unfortunately, many of these studies are not accessible for public or academic use. Most media polls are proprietary to their owners, and it is unclear whether they survived past the 1997 news cycle. The few polling companies operating in 1997 may have changed hands or become defunct. Today, it is difficult to find accessible raw data that allow analysis of pre-handover public attitudes about Hong Kong’s political future. Among those better-documented polls, many were designed to capture quick snapshots of public opinion, with a small sample size of “500 plus”[4] as the standard and few questions beyond demographics.

Roper Center Data

To address these challenges, I analyzed a public opinion survey conducted by Asian Commercial Research under commission of the United States Information Agency (USIA) only 4 months before the handover.[5] Compared to many studies fielded at the time, the USIA data collected a large sample of more than 1,000 respondents and included a long list of attitudinal questions.[6] The data are currently archived at the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research.

The poll was conducted by ACR via telephone interviews between March 5 and March 11 1997, yielding 1055 completes.[7]

Compared to contemporaneous polls, the USIA data included a wider set of attitudinal questions that measured respondents’ confidence about Hong Kong’s economic and political continuity after the handover, their views on international affairs, and their perceptions about the United States’ role in Asia, in addition to standard demographic questions.

In particular, the USIA survey asked the same “controlling history” question used in the HKTP studies that captured preferences regarding Hong Kong’s political future:

If you were controlling history, what would you most like to happen in 1997?

Hong Kong to stay part of Britain, as now?

Hong Kong to become a self-governing country and a member of the British Commonwealth?

Hong Kong to become a completely independent nation?

Hong Kong to become, as planned, a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China?

This question measures what HKTP terms “fundamental preference”,[8] which differs from other poll questions that gauge the public’s current mood about the handover.[9] By asking respondents to imagine they were “controlling history” and state what they would most like to happen, the question differentiates those who were genuinely hopeful about joining China from those who saw it as an unwelcome but tolerable outcome. Those who lack a fundamental preference for joining China might show less patience for economic and governance blunders, which can pose governance challenges to the post-97 administration.

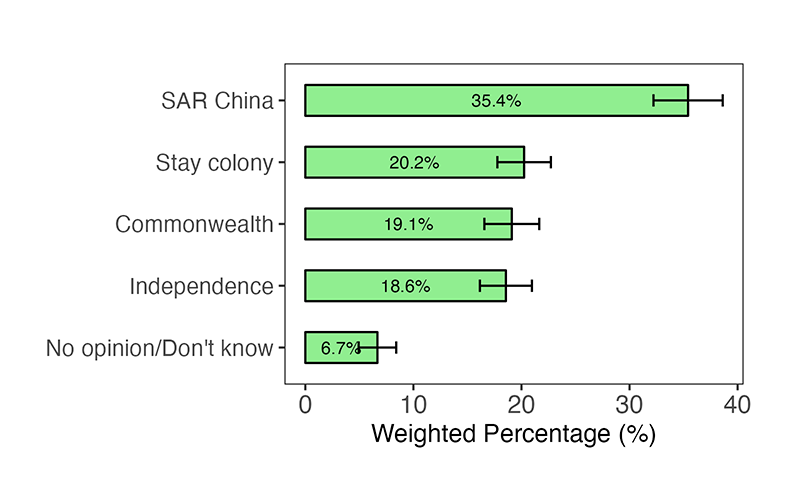

The percentages are shown in Figure 1 with 95% confidence intervals. The March 1997 survey recorded lower support for the Special Administrative Region (SAR) option compared to the longitudinal HKTP surveys, but it remained the most popular option at 35.4%. This figure is corroborated by HKTP’s survey two months later, which recorded a close percentage of 42% support for SAR, a substantial drop from the unusually high estimate of 62% in February.[10]

Preferences for alternatives–independence, staying as a colony, or joining the Commonwealth–were all individually lower compared to joining China. But combined, 57.9% of those surveyed expressed preference for a trajectory different from joining China. In other words, on the eve of the handover, those who would rather Hong Kong pursue alternative pathways–however politically impossible they were–still outnumbered those who preferred the planned path.

Nevertheless, it is important not to overstate actual support for these alternative pathways. Though returning to China as an SAR was not the majority’s top choice, there were no serious attempts to push for independence, staying as a British colony, or joining the Commonwealth as an independent state. Other polls at the time reported that most in Hong Kong were feeling cautiously optimistic–or at least indifferent–about the handover, a political reality they had accepted as fact.[11]

Who Wants to Return to China?

On the flipside, however, those who said they would prefer Hong Kong to join China as an SAR, were likely those who felt the most enthusiastic about this prospect. Who were those most optimistic about joining China, and what explains their optimism?

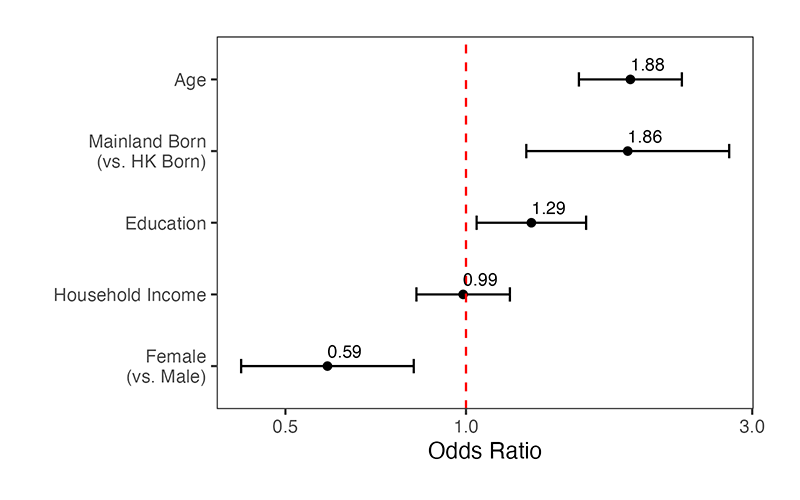

To answer this question, I first present the results of a logistic regression that uses demographic factors as predictors and whether the respondent chose the SAR option as the outcome.[12] A logistic regression has the advantage of showing how each demographic factor associates with the likelihood of choosing the SAR option, while controlling for the influence of other variables. The data includes information on respondents’ sex, household income, birth place, age, and education level (below primary, primary, secondary, university or higher).

The findings expressed in odds ratios are shown in Figure 2. The non-binary predictors (age, household income, and education) were standardized, so that the odds ratios represent the effect of a one standard deviation increase in each of these variables on the odds of preferring that Hong Kong joins China.

Older individuals, those born in mainland China, and those with higher education had higher odds of expressing the preference of joining China. Household income had no significant effect, and women were less likely to hold this preference.

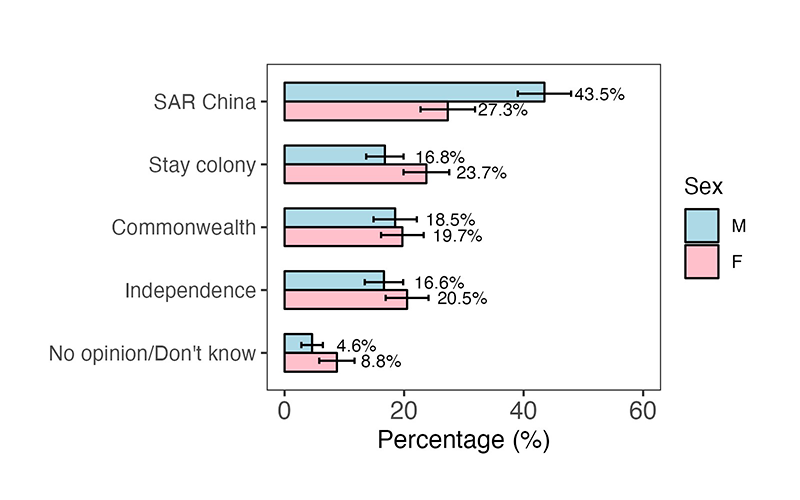

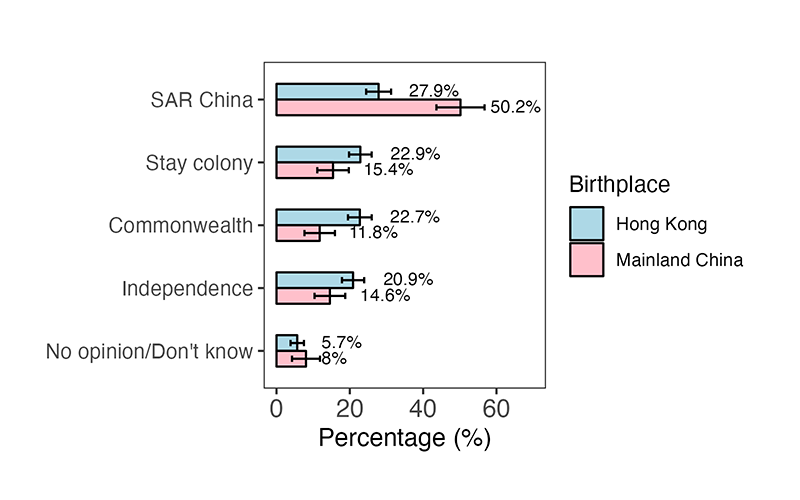

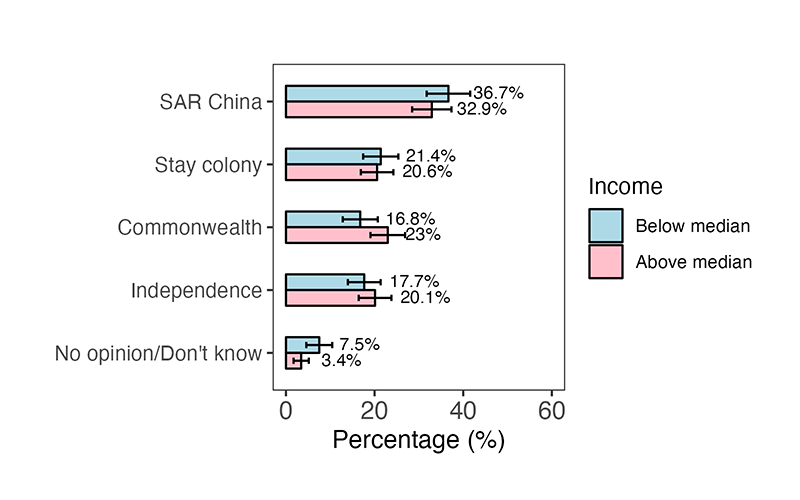

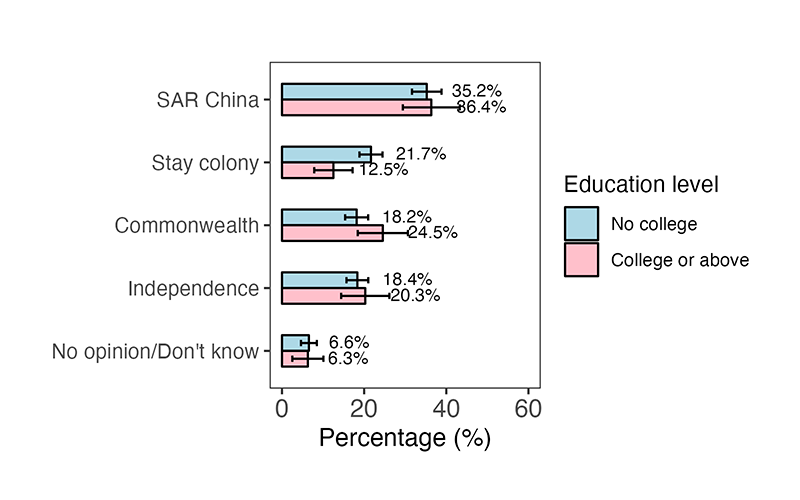

While estimates of a logistic regression have the advantage of controlling potential confounders, they do not convey the more intuitive finding, which in this case is the size of the percentage of respondents in each group. To visualize the effects more intuitively, I also create side-by-side bar plots to show the percentage of respondents in each demographic group who preferred each pathway option. For simple interpretation, I show the weighted percentages with 95% confidence intervals, but without controlling for other variables.

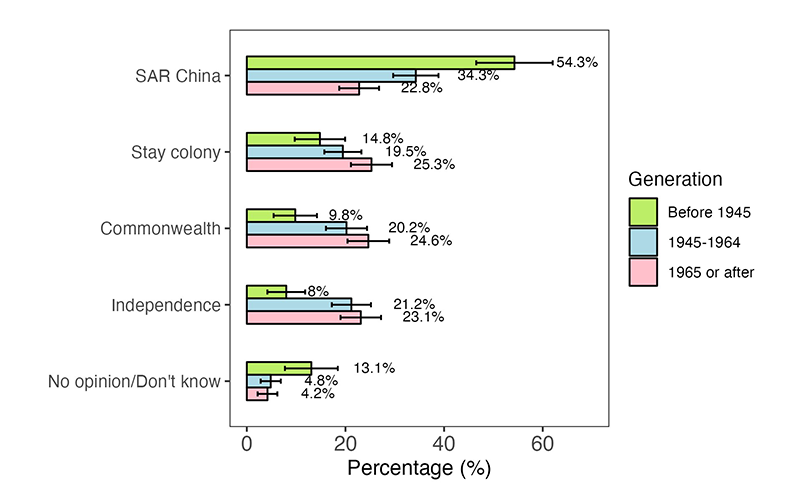

Figures 3 to 7 show the weighted percentage preference for the four potential pathways, broken down by age, sex, birthplace, income, and education. These plots are more informative than results of a logistic regression because they show the percentage support for each pathway, without having to collapse the response into a binary variable.

The age variable was transformed into generational groups based on the common categorization of pre-WWII generation (born before 1945), postwar baby boomers (1946-1964), and Gen X (1965 or after).[13] The education variable was collapsed into an indicator of whether the respondent was college-educated, whereas the household income variable was transformed to indicate whether the respondent’s household income was above the median monthly household income of HKD$19,000 in 1997.[14] Since the income data in the survey was divided by HKD$5,000 intervals, I used HKD$20,000 as the cutoff.

The results point to the potential role of personal and familial ties to China in shaping one’s fundamental preference. Supporters of joining China were more likely to be born before WWII and those who migrated to Hong Kong from the mainland. While the data did not include information about respondents’ self-reported identity,[15] the older and mainland-born demographic was likely one that had stronger ties to a Chinese identity from kinship and familial bonds, as many in the “silent generation” were Chinese migrants and refugees fleeing political turmoil in the mainland and saw Hong Kong as a refuge. In contrast, those born after World War II and in Hong Kong had developed a stronger local identity, as their identity was largely shaped by the social and political life in Hong Kong.

The gap in support between men and women was substantial and consequential. Men were much more likely to support joining China than women, while women appeared to have a slightly higher preference for the colonial status quo. As Michael E. DeGolyer observed, though women expressed markedly different preferences than men, the disproportionate representation of women in the Preparatory Committee (8 women out of 150 members) appointed by Beijing was unlikely to reflect societal voices fairly.[16]

While education also played a role, college education seemed to be associated only with a rejection of continued British colonization, rather than a clear agreement on a more desirable path. Their rejection of colonization may be a result of broader exposure to global trends in decolonization at the time. However, such exposure did not necessarily translate to support for joining China, perhaps due to reservations about civil rights and autonomy. Household income did not appear to play a clear role in preferences about Hong Kong’s path.

Economy Euphoria and Freedom Fears

What does the USIA data tell us about the potential reasons why individuals prefer to join China? While the strong effects of age and birthplace suggest cultural and political identity as possible factors, the USIA survey did not include self-reported identity questions for analysis. The survey did, however, contain questions about respondents’ perceptions of changes to Hong Kong’s economy, freedoms, and governance after 1997. These questions allow us to examine whether common concerns about the economy and political freedoms were associated with fundamental preference.

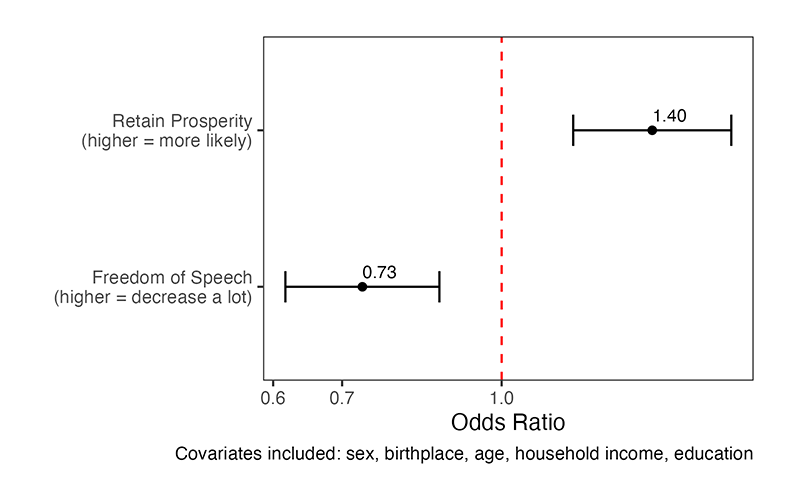

I focus on two questions that were highly relevant to individuals’ attitudes towards joining China: confidence in Hong Kong’s continued prosperity after 1997 and expected changes to Hong Kong’s freedom of speech.[17] These concerns formed the basis of individuals’ confidence toward the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ framework, which was a crucial factor in garnering support for the first SAR administration following the 1997 handover.

- How likely do you think it is that Hong Kong will retain its prosperity in the coming years – very likely, fairly likely, not very likely, or not likely at all?

- There has been a lot of debate about what our life will be like after the resumption of Chinese sovereignty. After July, do you expect freedom of speech in Hong Kong to increase, decrease or stay the same? Do you think it will (increase/decrease) a lot or a little?

I expect that those who support joining China should be more confident that Hong Kong would retain its prosperity and less worried about Hong Kong losing its freedom of speech. Figure 8 shows the results of a logistic regression with support for joining China as the outcome, and both the ‘retain prosperity’ and ‘changes to freedom of speech’ variables and demographic variables included as covariates.

As expected, both variables were associated with the likelihood of selecting ‘joining China as SAR’ as the preferred path, though these associations were small in magnitude. Those who believed Hong Kong was likely to retain its prosperity were more likely to prefer joining China, and those who worried that freedom of speech would decrease were less likely.

These results are unsurprising and reflect societal discourse about the handover at the time. A more interesting question is whether the effects of economic confidence and rights concerns on the ‘join China’ preference were even across demographic groups. In other words, do these concerns affect different individuals’ support for joining China equally? Uneven effects may suggest that Beijing’s attempts to reassure individuals of Hong Kong’s continued prosperity and political distance only worked for some members of the public but not others.

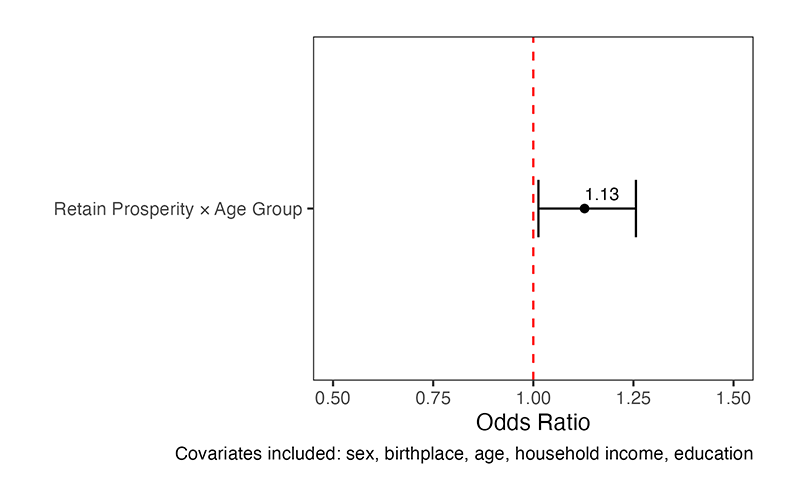

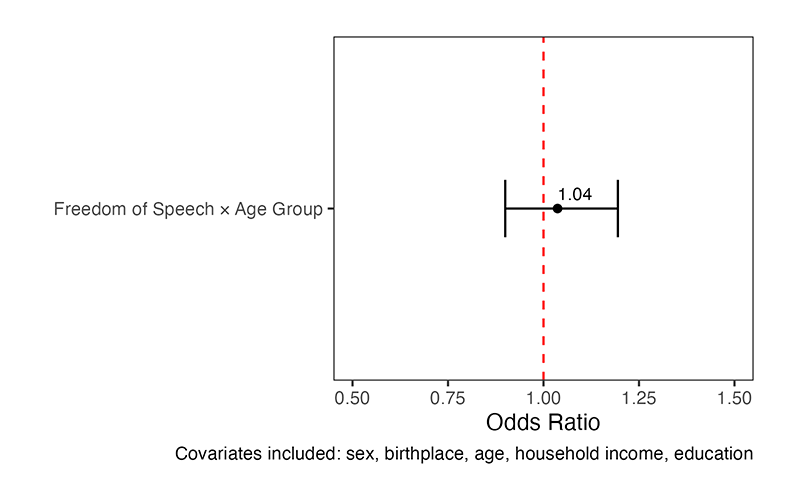

Figure 9 illustrates how the effects of economic security vary by age. I used a logistic regression that predicts the likelihood of preferring to join China with an interaction term of ‘retain prosperity’ and ‘age’, along with other covariates as controls. The interaction term is significant and positive, suggesting that the influence of economic confidence on respondents' support for joining China was stronger among older generations. In contrast, Figure 10 shows that concerns about freedom of speech did not have varying effects on joining China across different age groups.

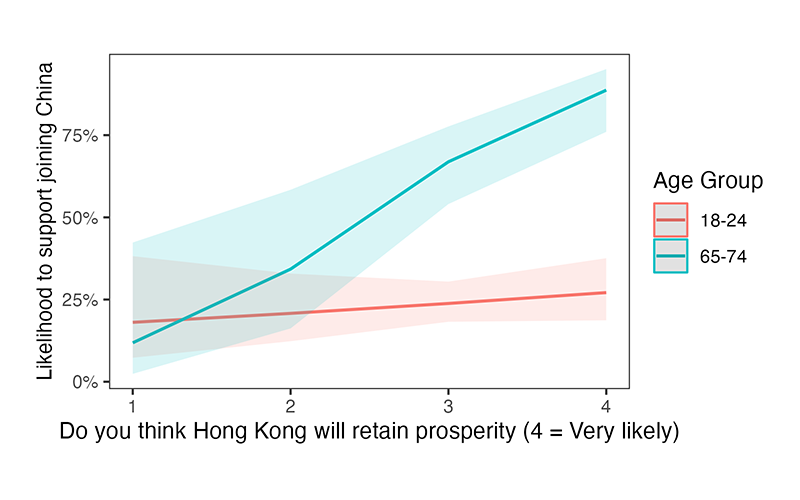

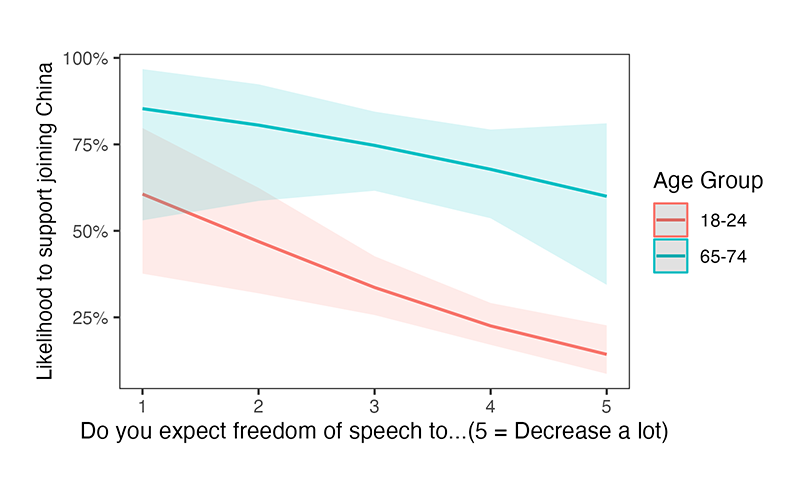

A more visual representation of these results using predicted probabilities is shown in Figures 11 and 12, using the youngest (18-24) and the oldest (65-74) age groups as reference points.

As seen in Figure 11, as respondents’ confidence in Hong Kong's future prosperity increases, the likelihood of supporting integration with China rose only for older respondents, while the younger respondents stayed the same in their preference for China. Older individuals appear more responsive to positive economic assurances in their support for reunification with China, while younger individuals show a relatively stable, lower level of support regardless of their economic outlook. For the younger generation (Gen X), their reluctance toward joining China could not be easily explained by economic expectations.

On the other hand, Figure 12 shows that both younger and older generations exhibited a similar decrease in their likelihood of supporting joining China as they perceived a greater decline in freedom of speech. This indicates that fears about the erosion of civil liberties (exemplified here by the freedom of speech) were a common and widespread concern, suggesting the difficulty in garnering broad-base support for integration without addressing concerns about civil liberties.

From Polls to Politics

Public opinion polls are intricately tied to colonial governance and international politics. The advent of scientific polling firms provided valuable data for state actors to inform policy. One recently published work by historian Florence Mok investigated how the colonial government set up opinion-listening infrastructures and commissioned scientific polls during the transitional period.[18] The poll analyzed in this study highlights the role of public opinion in informing policy outside of colonial Hong Kong, especially the U.S.’s Hong Kong Policy Act.[19]

Historical public attitudes in 1997 provide a lens into Hong Kong’s aspirations and worries for its political future, some of which still echo today. Large-scale protests in 2019 were a warning sign that the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ framework had lost its appeal to many, especially the young generation born after 1997. My analysis shows that a generational divide was already present in 1997, despite the fact that the ‘young’ generation in 1997–at the time politically active and hopeful–has today become more conservative and pro-establishment.[20] The players may have switched sides, but the pattern remains.

The enduring relevance of these historical attitudes underscores the importance of preserving historical public opinion data. As Hong Kong draws international attention for large-scale protests in 2019 and the subsequent crackdown, it becomes ever more relevant to understand the historical roots of current discontent. Continued efforts by historians and social scientists to catalogue, uncover, and analyze these studies will prove fruitful to inter-disciplinary knowledge discovery.

[1] I thank Jacqueline Liu and Brian O’Keefe for generous feedback.

[2] Robert T.Y. Chung, “Public Opinion,” in The Other Hong Kong Report 1994, ed. Donald H. McMillen and Si-Wai Man (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1994), 105.

[3] “More Support for Beijing Rule, Says Poll,” South China Morning Post, December 12, 1994, https://www.scmp.com/article/99486/more-support-beijing-rule-says-poll.

[4] Chung, “Public Opinion,” 107.

[5] United States Information Agency (USIA), “USIA Poll # 1997-I97012: Hong Kong’s International Relations” (Cornell University: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, 1997), https://doi.org/10.25940/ROPER-31084510.

[6] The USIA was a Cold War-era foreign affairs agency responsible for supporting U.S. foreign policy interests abroad through public diplomacy and information programs. Colonial Hong Kong served as a key listening post for Anglo-American intelligence services in East Asia and a base for both covert and overt information operations. Toward the end of Hong Kong’s colonial status, the U.S. closely monitored Hong Kong’s transition to ensure U.S.-Hong Kong economic relations could continue. For a survey of USIA’s activities in Hong Kong, see Chi-Kwan Mark, Hong Kong and the Cold War: Anglo-American Relations 1949-1957 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[7] The sample was obtained by first calling households based on a probability-based selection of numbers from a telephone book, then interviewing individuals eligible to fill census-based quotas on age group, sex, and region. The survey includes weights to account for over- or under-achieved quotas. All analyses in this blog post except Figured 11 and 12 were calculated with weighted data.

[8] DeGolyer, “Political Culture and Public Opinion.”

[9] For example, questions that asked respondents to choose an adjective (e,g, “glorified”, “excited”) that expressed how they felt about the handover. See “Graft Greatest Worry in Future Reveals Poll,” South China Morning Post, June 18, 1997; “Survey Finds Perception Gap in U.S., Hong Kong Expectations,” Associated Press, April 26, 1997.

[10] “Graft Greatest Worry in Future Reveals Poll.”

[11] HKTP’s February survey recorded that 62% felt optimistic or very optimistic about the reunion, while 30% felt indifferent. See Hong Kong Transition Project, “Hong Kong: Bridge to the Future,” Media Briefing, June 17, 1997.

[12] Those who answered “No opinion / Don’t Know” were excluded from the analysis.

[13] For a discussion on political generations in Hong Kong, see T.Y. Wang, “Generations, Political Attitudes and Voting Behavior in Taiwan and Hong Kong,” Electoral Studies 58 (April 2019): 80–83, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.12.007.

[14] “Table 130-06102 : Statistics on Domestic Households,” Census and Statistics Department, accessed December 1, 2024, https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/web_table.html?id=5&full_series=1&download_excel=1.

[15] Typically captured by this question: “What do you consider yourself to be? (Hong Kong Chinese, Chinese, Hong Kong people, Hong Kong British)”. See DeGolyer, “Political Culture and Public Opinion,” 189.

[16] Michael E. DeGolyer, “Public Opinion on Hong Kong’s Transition,” in Institutional Change and the Political Transition in Hong Kong, ed. Ian Scott (Hampshire: Macmillan, 1998), 45.

[17] I conducted a separate exploratory factor analysis (EFA) that identified economic concerns and worries about political rights as the top two significant factors in the survey questions. While the results of the EFA are not reported here due to space constraints, the results of this section are robust to using factor scores as substitutes for ‘retain prosperity’ and ‘freedom of speech’. Factor scores include more information from adjacent variables that measure similar concepts. For example, the ‘economy’ factor also explains confidence that U.S. investors would stay in Hong Kong after 1997, and the ‘rights’ factor also explains freedoms of assembly and the press.

[18] Florence Mok, Covert Colonialism: Governance, Surveillance and Political Culture in British Hong Kong, c. 1966-97 (Manchester University Press, 2023).

[19] U.S. Department of State, April 14, 1997. “United States-Hong Kong Policy Act Report, as of March 31, 1997”

[20] For one example, see Kevin Tze-Wai Wong, Victor Zheng, and Po-San Wan, “Sources of Public Support for the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement in Hong Kong: Localism or Others?,” Journal of Contemporary China 33, no. 147 (May 3, 2024): 432–47, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2023.2187692, 444.