Ten years after Hurricane Katrina, the rebuilding continues. Indeed, rebuilding carries on in communities all over the country - in New York and New Jersey coastal neighborhoods hit by Sandy, in western towns destroyed by wildfires, in the Irene-ravaged small towns along the rivers of Vermont. After Superstorm Sandy wreaked her destruction, the New York Times fretted that “tax money will go toward putting things back as they were, essentially duplicating the vulnerability that existed before the hurricane." Experts may be concerned about this cycle of devastation and reconstruction, but what does the public think? From the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research Archives:

Hurricane Floyd: A divided country

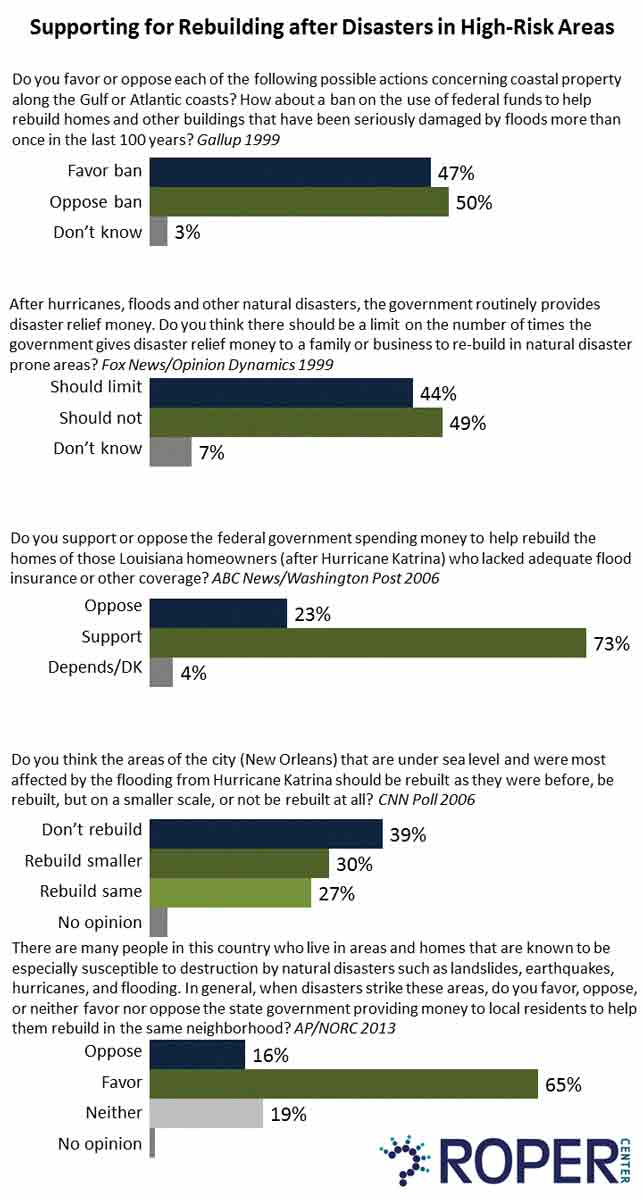

The first time the public was asked their willingness to pay to rebuild after a disaster was following the flooding caused by Hurricane Floyd in 1999. The country was nearly evenly divided on whether federal funds should be banned from being used to rebuild homes and other buildings that have been seriously damaged by floods more than once in the last 100 years. Similarly, 44% of the country believed there should be a limit on the number of times the government gives disaster relief money to a family or business to re-build in natural disaster prone areas; 49% disagreed.

Katrina: Rebuild the Big Easy

Perhaps the shock of seeing American citizens trapped for days in flooded New Orleans made Americans particularly sympathetic to rebuilding after Katrina. In June 2006, 73% of the country supported the federal government spending money to help rebuild the homes of those Louisiana homeowners who lacked adequate flood insurance or other coverage to rebuild after Katrina. Even when a price tag of $7.5 billion was specified, 66% were in support. An August poll that year found a somewhat higher level of skepticism about rebuilding. When offered three options, a plurality of 39% said “areas of the city (New Orleans) that are under sea level and were most affected by the flooding" should not be rebuilt at all. But a 57% majority said they should be rebuilt either as they were or on a smaller scale. Residents of the city also wanted to see the Big Easy rebuilt. A 2007 Kaiser Family Foundation poll of New Orleans residents found only 19% thought the low-lying areas of New Orleans should not be rebuilt, 75% thought they should. When offered three options by Gallup/USA Today, as in the national CNN poll, just 12% of New Orleans residents said not to rebuild at all, while 43% said rebuild as before, and 41% on a smaller scale.

Sandy: Support for rebuilding after disasters - even more than for relocating

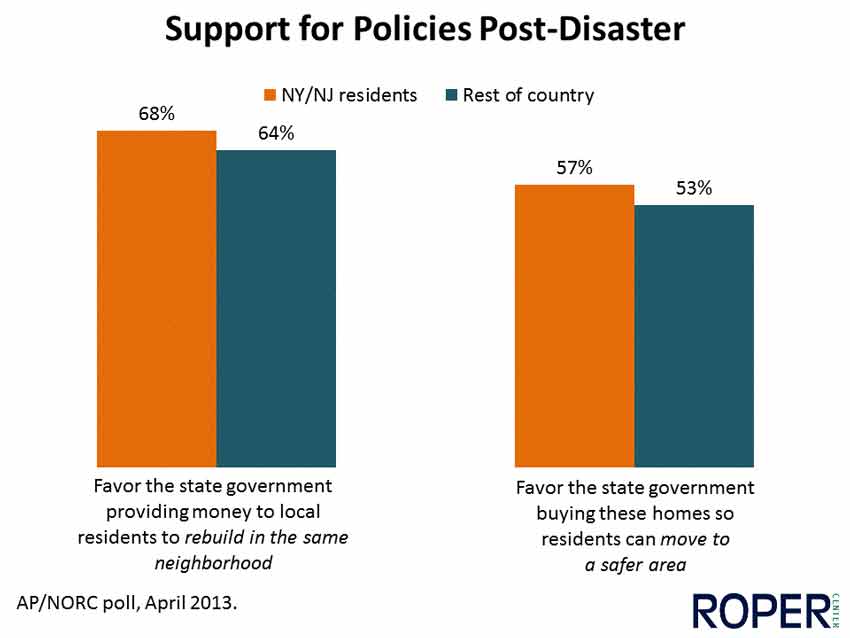

An AP/NORC poll conducted after Hurricane Sandy, both nationally and in the affected regions of New York and New Jersey, asked people what they thought should be done in general to help people who live in disaster-prone areas after catastrophe strikes. The poll found that about two-thirds of both NY/NJ residents and the rest of the country favored the state government providing money to local residents to rebuild in the same neighborhood. Slightly lower numbers favored the state government buying these homes so residents can move to a safer area.

Risks to the ties that bind

Risks to the ties that bind

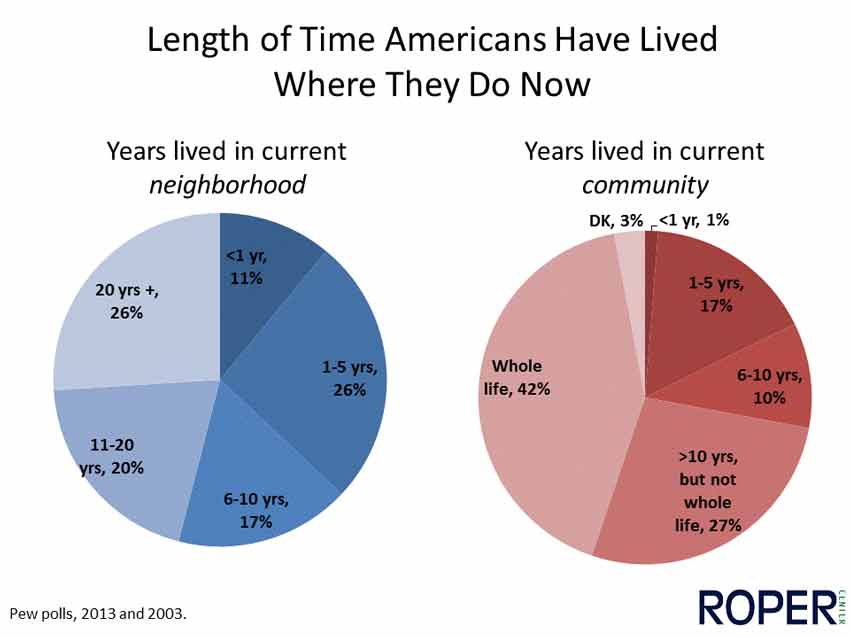

A sense of personal vulnerability may play a role in the public's willingness to support rebuilding efforts. Over four in ten in a 2013 Yale/George Mason University poll considered it very or somewhat likely that their own community would suffer a natural disaster caused by extreme weather in the next year. If such an event were to occur, most Americans say they would want to rebuild. In a national Gallup/CNN/USA Today Poll taken two weeks after Katrina, respondents were asked what they would do if their homes were destroyed and communities ruined by a natural disaster. Despite the devastating images of a city underwater, 65% said they would rebuild, while 32% said they would move. Though Americans are often considered highly mobile, polling shows that most of the public have strong ties to their communities, which means relocation could take a major emotional toll. A 2003 poll found that 41% of Americans had lived in their current communities their whole lives. Another 29% had lived there more than ten years. Connections to particular neighborhoods also run deep. In a 2013 poll, 46% of respondents said they had lived in their current neighborhood for over 10 years.  In the AP/NORC post-Sandy survey, 64% of respondents nationally agreed that their neighborhood was “close-knit." In a 2014 AP/NORC poll of people who lived in neighborhoods affected by Hurricane Sandy, 75% of those who had been living in the neighborhood during the storm said that their neighborhood had been close-knit. These connections may also be deepened by the experience of living through a natural disaster. In the same poll, 36% of those who had lived through Sandy said they met neighbors for the first time as a result of the storm. A third said people in their neighborhood were a little or a lot closer to their neighbors than before the storm.

In the AP/NORC post-Sandy survey, 64% of respondents nationally agreed that their neighborhood was “close-knit." In a 2014 AP/NORC poll of people who lived in neighborhoods affected by Hurricane Sandy, 75% of those who had been living in the neighborhood during the storm said that their neighborhood had been close-knit. These connections may also be deepened by the experience of living through a natural disaster. In the same poll, 36% of those who had lived through Sandy said they met neighbors for the first time as a result of the storm. A third said people in their neighborhood were a little or a lot closer to their neighbors than before the storm.

There's no place like home

The experience of those who have lived through such disasters bears out Americans' expectations of their own preferences in these circumstances. Historically, even following the most catastrophic events, the majority want to return to or remain in their homes. After Hurricane Andrew in 1992, despite $25 million in damages in Dade County, almost no county residents in a CBS News/NYT poll said they planned to relocate; 92% planned to stay in the area. One month after Katrina, a Gallup/CNN/USA Today/American Red Cross poll of hurricane survivors found 51% already had returned to their homes. Almost three in ten (27%) said they definitely or probably would return. Only 8% said they would definitely not return to the community where they lived before the storm hit, and 11% said they probably would not. Those affected by disaster in high-risk areas are aware of the dangers involved in returning. A 2015 Kaiser Family Foundation/NPR poll of New Orleans residents found that 34% were very worried, and 33% somewhat worried, that another hurricane would hit and cause similar or worse damage than Katrina. But that fear is not as powerful as the ties the bind people to their communities and homes.