But how did it work?

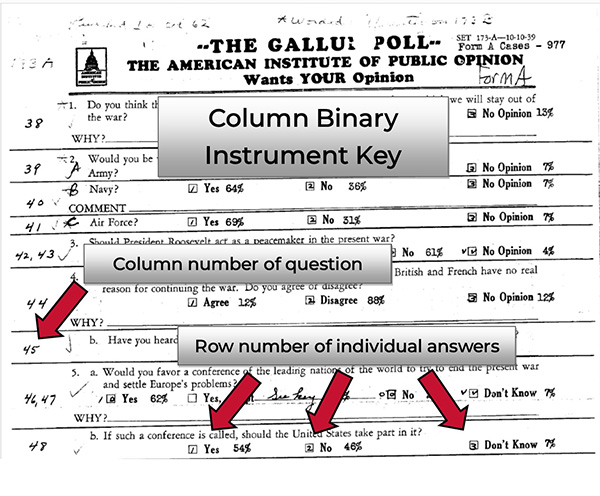

A punch card consisted of 80 columns and rows numbered 1-9, plus three additional rows which are usually given the names X, Y, and Z. Each location on the card indicated a data value in a binary form. For example, a question might have three possible responses:

Which side do you think will win the war?

A. Germany

B. England and France

C. Don’t Know

The results for this particular question were entered in column 40. Cards for respondents who answered “Germany” received a punch in the first row, “England and France” in the second, and “Don’t know” in the third. This key would be handwritten on a blank questionnaire, indicating that the answers to Question 4 were located in Column 40, 1-3.

Simple enough as it goes; however, there were complications brought on by the cost of punch cards. To lower expenses, polling organizations made use of all the space on a single card, rather than reserving a single column for a single question. Therefore, the next question in the survey might have responses coded in Column 40, 5-7. This tactic is known as a “multi-punch.” Some organizations utilized the gaps on an otherwise full card by inserting a late question with response categories punched across several columns and rows, wherever they could find a space.

Sometimes organizations would make the most use of a single set of punch locations by entering different branches of follow-ups to a filter question into the same location on the punch card. The “meaning” of the punch – the response code that went with it – would change based on the respondent’s answer to the earlier question. In some cases, punches across multiple columns were used to represent a single multi-digit number, the first digit being the punch location in the first column, the second in the next, and so on.

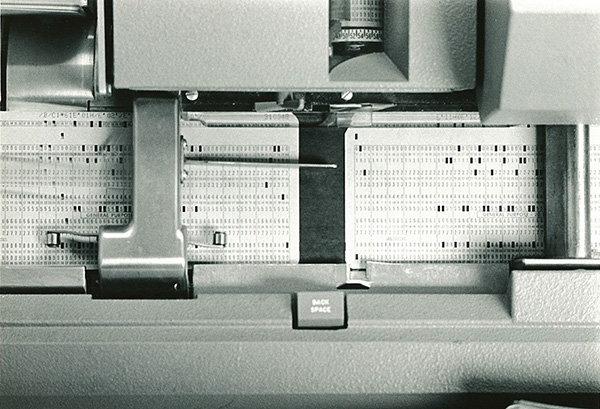

Here are some cards being coded in 1939:

Column binary files were the earliest files that preserved the data resulting from keypunching. Column binary is in many ways an excellent preservation format, holding a large amount of data in a relatively small file, and the data can be read today by some statistical programs. But a great deal of work needs to go into the interpretation of the documentation in order to make sense out of the data.

At the Roper Center, an internally developed tool is used to convert the original column binary dataset into an SPSS dataset in which each and every keypunch becomes a single variable. To make this dataset functional for users, our data processors need to interpret the documentation and identify which variables need to be merged together to represent the results of a single question. They may also need to break some data apart, creating multiple variables when a single punch location was used to represent various possible answers. Data labels also need to be added, and stray, undocumented punches accounted for. After the conversion is completed, frequencies are run and compared to contemporaneous reporting of results whenever available, then the new dataset undergoes a quality review by a different member of the team. Our column binary team members are experts in untangling the knots of these old files.

This process can take several days or even several weeks. But the end result is a functional modern dataset that opens up the past for researchers of today and ensures that the voices of the people who participated in early survey research are preserved for the future.

Found a dataset in the collection you want to use, but it’s in column binary? Request a conversion from our data services team here.