PUBLIC ATTITUDES TOWARDS MILITARIZING LAW ENFORCEMENT: THE CASES OF MEXICO AND GUATEMALA IN THE 1990s

Jessica Zarkin

On January 2017 the president of Guatemala, Jimmy Morales, announced that by mid-2018 he would be withdrawing the military from police duties all throughout the country (see Figure 1). Many international organizations applauded Morales’ effort to demilitarize citizen security primarily because they considered military intervention in policing problematic. However, just days after the announcement, it became evident that some people were not as happy with the decision, nor were the international organizations. During interviews with news reporters, some citizens claimed that withdrawing the military was a terrible decision not only because soldiers were the only ones capable of protecting them, but also because the police could not be trusted (Alay 2017). [i]

The contrasting response between organizations applauding demilitarization and citizens angered by the decision raises some interesting questions as to how people view the military’s role today. Considering that the military is also conducting policing operations in 12 other countries in the region, it is urgent that scholars understand whether Latin Americans support the military’s intervention in fighting crime, and if so, why they support militarizing security operations.

FIGURE 1. Soldiers patrolling the streets of Guatemala

The Roper Center’s collection of public opinion surveys in Latin America provide a unique opportunity to answer the questions posited above. The Center currently holds countless surveys sponsored by the United States Information Agency (USIA) fielded during the end of the 1980s and during the 1990s. These surveys included questions on Latin American attitudes towards democracy, foreign powers, civil war, economic crises, and anti-drug policies. Though many of the USIA polls included questions on how to best tackle drug-related issues (consumption, trafficking, and production), in many occasions the police and the military ended up grouped in the same answer-choice. [ii] However, some USIA surveys did ask respondents their opinion on military action in anti-drug and anti-crime campaigns. Using data from the USIA 1992 poll in Guatemala and the USIA 1997 poll in Mexico, in this article I explore the determinants of support for militarizing law enforcement, precisely when militarization was beginning to unfold in Mexico and about to go on a four-year hiatus in Guatemala –somewhat similar to what is happening today.

Guatemala

In 1992 Guatemala was at the end of a 36-year long civil war between leftist guerillas and the military regime that resulted in more than 200,000 people killed and hundreds of thousands of displaced. [iii] By 1994, peace talks between the government and the rebels started, rebels declared a cease-fire, and the civil war ended with the signing of the 1996 peace accords. The accords called for extensive political and economic reforms, including greater participation of civil society, an increase in health and education spending, multilingual courts and school programs, the solution of land conflicts, and human and indigenous rights. What is more, the accords also made way for the creation of a professional civil police force, and the demilitarization of public safety. Demilitarization meant removing the military from the streets and limiting the functions of the army to border security and protecting sovereignty. However, no more than four years passed before the army was again deployed for internal security purposes under president Alfonso Portillo (2000-2004). For Portillo, the country’s homicide rate –which averaged 35 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants during the second half of the 1990s– justified re-militarizing domestic security.

It was in this larger context that Guatemalans were asked to express their views on the regime, on the government, on the military and how to best handle crime and drug trafficking. It is surprising that even though military forces had engaged in violent and widespread repression for more than 20 years, and that the country was still under indirect military rule, close to 30% of the population still thought that a military regime was best for the country and 38% believed things were going well. As for issues related to crime and drug violence, only 15.8% of respondents mentioned crime and violence as the most important problem in the country –compared to 52% today. [iv] Yet despite the low salience of crime in people’s mind, over 67% agreed that the armed forces should participate in anti-drug campaigns.

Who was most likely to endorse the military’s participation in policing operations? Using a logistic regression analysis, I find that socioeconomic status, preference for a military regime, ethnicity and geography are all associated with support for militarizing law enforcement. Interestingly enough, neither beliefs about crime salience, beliefs that military regimes are better at protecting people from crime and violence, perceptions of neighborhood safety, education, age, gender, and overall assessments on government performance are related to support for militarization.

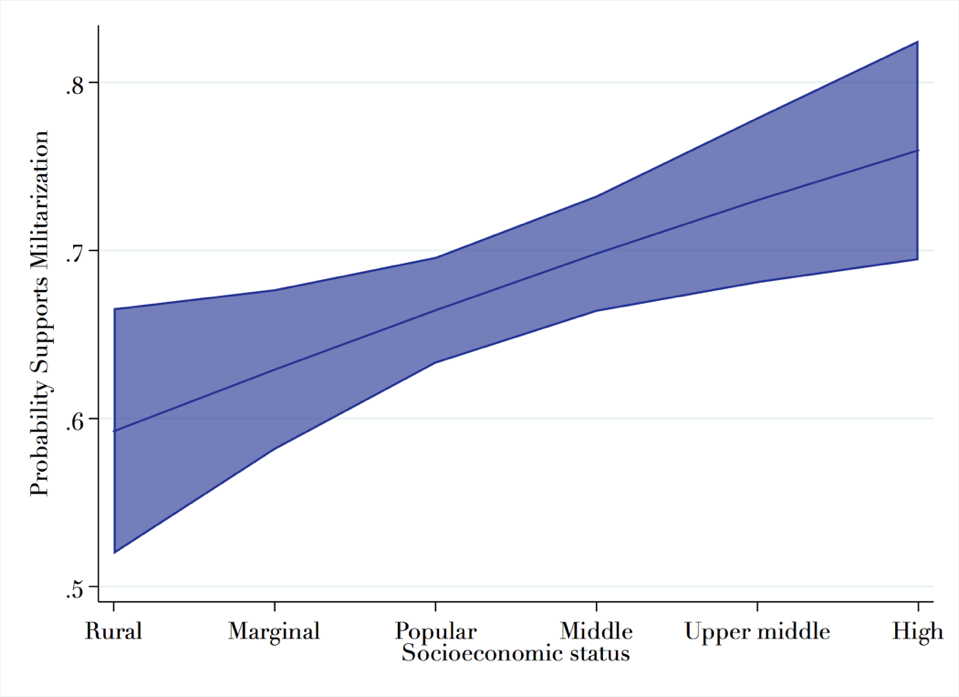

Specifically, preferring a military regime over a democratic and a revolutionary regime increases the probability by 65 percentage points. Living in the capital, Guatemala City, increases the probability by 122 percentage points. Being an indigenous Mayan decreases the probability by 42 percentage points. Lastly, as Figure 2 shows, moving up one social class increases the probability by 17 percentage points.

Figure 2. Probability of support for militarization by socioeconomic class

Overall, these results suggest that the Guatemalans least likely to endorse the military’s continuous role in domestic security were the most exposed to state violence during the civil war. State violence was concentrated in the Mayan-dominated villages of the Western highlands (between Chimaltenango and Huehuetenango).[v] On the contrary, high-income residents of Guatemala City –that is, the least exposed to the state’s repressive terror campaigns– were most likely to support the military’s role in domestic security. A Mayan male from rural Guatemala had a 44 percent probability of supporting military deployment, while a non-Mayan male from the capital had an 87 percent probability of doing so.

Mexico

In 1997, Mexico was in a very different situation to that of Guatemala’s. The country was in a difficult road to stability. It was in the midst of a transition to democracy that would bring to an end 70 years of the Institutional Revolutionary Party’s (PRI) authoritarian rule. Moreover, it was also emerging from one of the worst economic crises in decades (the 1994 Mexican Peso crisis). Beyond these big economic and political developments, things were also changing considerably in the security arena. On the one hand, the Federal Police was undergoing a process of increasing militarization which would culminate in the creation of the Federal Preventive Police (Policía Federal Preventiva or PFP in Spanish). [vi] On the other hand, by 1996 the armed forces were openly participating in policing operations as part of President Zedillo’s (1994-2000) new strategy to fight organized crime. [vii] This militarizing trend continued under President Fox (2000-2006) with actions like Operation Safe Mexico and intensified in 2006 with President Felipe Calderon’s (2006-2012) declaration of war against the drug cartels. [viii]

It was under these circumstances that the USIA asked Mexicans to assess the government’s strategy to combat crime and the military’s new role in matters of public safety. In 1997, over 88% of Mexicans considered that crime and violence were serious problems in the country and only 48% rated the government’s efforts to control crime as very good or fairly good. Moving on to the security institutions involved, there was a clear divide between how Mexicans thought and possibly still do, about the military versus the police. While 71% had a fair to a great deal of confidence in the military doing what was best for Mexico, only 36% did for the local police. Even more, 56% thought that the military could do the best job at combating crime and violence compared to the federal police, local police, and other security organizations. Interestingly, 23% of respondents thought none of these organizations could do a good job.

Concerning the military’s participation in policing duties, over 53% of Mexicans knew that the armed forces were involved in combating crime and 29% knew they were involved in fighting drug trafficking. Regardless of whether they knew or not, 72% wanted the military to be deployed to fight crime and drug traffickers. Though this percentage is high, it is important to note that among those that said the army should be deployed to fight crime, only 1% felt very strongly about this statement, 5% felt somewhat strongly, 35% felt not very strongly, and 59% felt not at all strongly. Furthermore, close to 76% trusted that the military could do a good job at fighting street crime, and 49% said that if the military was deployed, they should be deployed to virtually everywhere in the country. Lastly, when asked as a forced-choice question, the percentage of respondents who thought militarization was acceptable comes down to 53%, and when asked what could be the biggest problem which might arise from using the military for policing duties, 29% named the military gaining too much power, 26% named corruption of the military and 28% the mistreatment of civilians.

Moving beyond this descriptive exercise, the next step is to ask who was most likely to support the military’s intervention to fight crime and drug trafficking. Using logistic regression, I find different patterns in Mexico compared to those described for Guatemala. [ix] First of all, there are no regional patterns of support for militarization. Living in Guadalajara, Mexico City, Monterrey, Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez made no difference. [x] Second, there is also no relationship between demographic characteristics and support. Just as in Guatemala, crime salience and gender are not associated with support for military deployment.

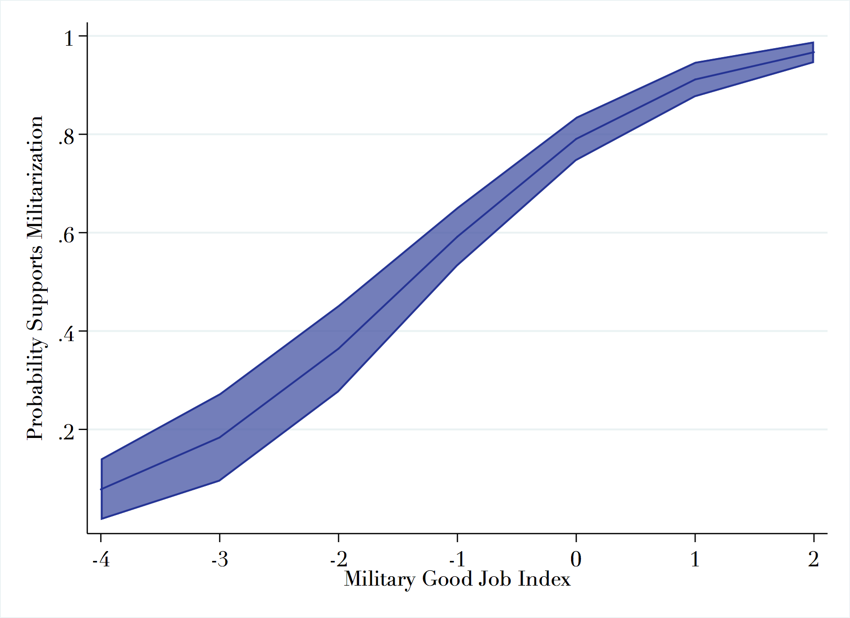

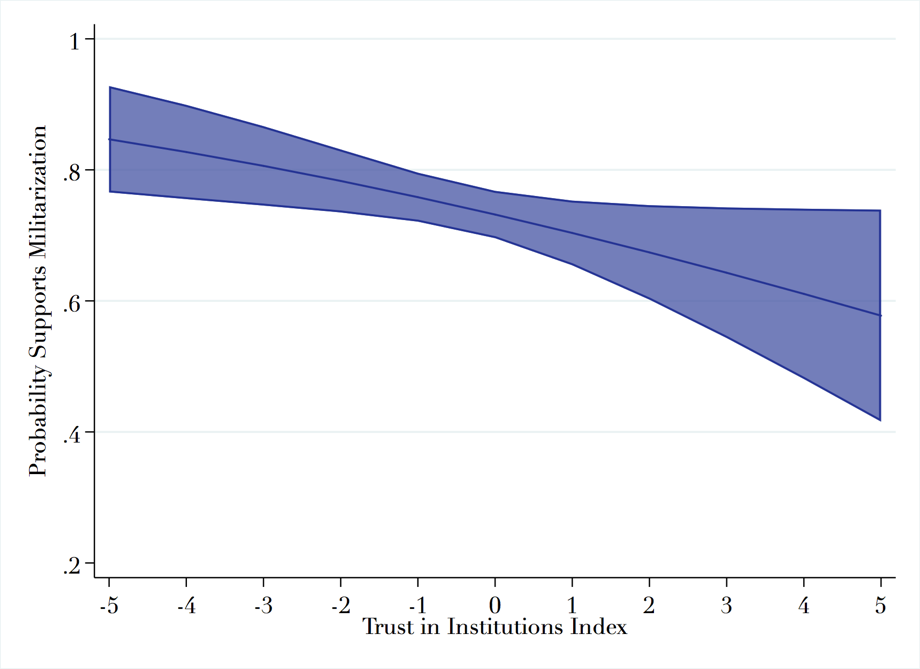

The two variables that are associated to support in Mexico are military effectiveness and institutional trust. Effectiveness is measured as an index with two components, whether the military can do a good job fighting crime and violence and whether they can do a good job fighting drug trafficking. Institutional trust is also an index of how much confidence people have in the federal government, the federal police, the counter-narcotics police, the justice system, and the local police. [xi] As plotted in Figure 3, a standard deviation increase in military effectiveness is associated with a 279-percentage point increase in the likelihood of support for military intervention. Moreover, a standard deviation increase in institutional trust decreases the probability of supporting militarization by 25 percentage points (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. Probability of support for militarization by Military Effectiveness Index

Figure 4. Probability of support for militarization by Institutional Trust Index

Who’s for and against (de)militarization today?

Reading about people’s discontent with seeing soldiers leave their neighborhoods in Guatemala prompted a series of questions as to whether this sentiment was common among the general public, if similar patterns existed across the region, and why would people want the military to intervene in domestic security. The results from the USIA 1992 poll in Guatemala and the USIA 1997 poll in Mexico provide us a couple of clues on how to begin to answer these questions. We now know that public support for militarization is fairly high and that the reasons why people endorse this strategy are more likely context specific. In the case of Mexico, it has more to do with institutional distrust and the loss of confidence in the police. In the case of Guatemala, there is a clear socioeconomic, ethnic and regional divide that seems to map onto the geography of state repression during the civil war.

It is also to be expected that these results might look different today, especially once we take into account that the military became more involved in domestic security and that criminal violence increased in both Guatemala and Mexico. However, it is also likely that generalized distrust and authoritarian legacies still play a large role in explaining why some citizens continue to call for the military to take action against criminal violence today.

Jessica Zarkin is a PhD Student in the Government Department (Cornell University). Shee was a Roper Center Kohut Fellow in the summer of 2018. To learn more about the Kohut Fellowship, click here.

Endnotes

[i] Alay, Alvaro. 2017. “Ejercito abandonara paulatinamente las calles y las avenidas.” PubliNews (February 5).

[ii] The question wording gives us some insight as to the lack of clarity between police and military work in the region. For example, the USIA 1991 poll in Ecuador asked respondents to choose the best strategy to solve the narcotrafficking problem in the country and offers as one response “increasing the number of police and/or military that actively combat narcotraffickers.”

[iii] The Guatemalan military assumed power in 1954 when Carlos Castillo Armas, backed by the CIA, declared a coup d’état and emerged as the provisional president. Castillo reversed land reforms that benefited poor farmers, took way the voting rights of illiterate Guatemalans and broke labor unions. These reforms resulted in civil unrest and by 1960 a rebellion to overthrow the military regime kicked off a bloody civil war that would last for 36 years long.

[iv] LAPOP 2016.

[v] Approximately 83% of the people killed during the Civil War were Mayans.

[vi] The PFP was created in 1999 by merging existing federal police agencies and transferring close to 5,000 soldiers from the 3rd military police brigade.

[vii] The military had been involved in combating drug trafficking all throughout the 20th C (for example, Plan Canador, and the Fuerza de Tarea Condor), primarily in drug crop eradication. However, their participation in fighting crime and drug trafficking increased significantly under Ernesto Zedillo’s (1994-2000) government.

[viii] Today over 67,000 soldiers participate in joint police-army operations in 24 out of 32 states in Mexico.

[ix] Of course, this could also be a product of the timing (1992 vs 1997), the difference in question wording, and the covariates used in the model.

[x] Though this was the case in 1997, this might not be the case for the last two decades given that criminal violence has largely concentrated in Northern Mexico.

[xi] Both indices were constructed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA).