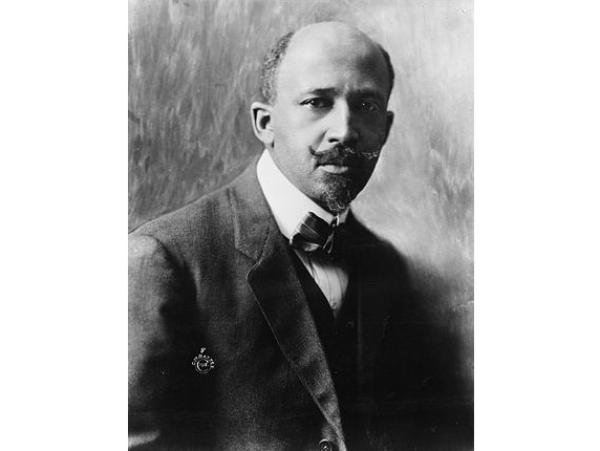

Du Bois’ work was in many ways far ahead of its time, in terms of both the methods he used and the topics he studied. When polling emerged as its own discipline from the merging of commercial marketing and academic research, the fledging field did not turn its attention to the Black American community for some time. National polls of the general public dominated polling for the first few decades of the industry, with relatively few national polls of any kind of subpopulation, though some polls exist of subpopulations within small geographic areas.

Early Period Polling

The lack of data makes studying black public opinion during the early polling period (1936-1947) extremely challenging. In addition, racist bias built into the polling instruments limits the ability to accurately analyze black opinion in the earliest polls. The Gallup Organization, which conducted the largest group of early polls and is the best source of early trends, used election participation as one of the most important criteria in setting quotas for their “national adult” polls. While the goal of understanding voters was understandable (and is still of interest to pollsters today), Black voices were systematically excluded from these polls because Blacks were not allowed to vote in the South and discouraged from voting in the North. These surveys contained fewer Black Americans than the general population, and often none in the South, where poll taxes and other voter suppression techniques prevented voting by Black Southerners. Fortunately, other polling organizations, like the Roper Organization and NORC, were interested in attitudes of the whole public, and the large sample sizes of these early quota polls allowed subpopulation analysis. Recent work by Adam Berinsky and Eric Schickler has generated survey weights to help researchers make more accurate inferences when using these data.

Although these surveys are of great historical value, because they offer an unparalleled glimpse into attitudes toward and among Black Americans at the time, the surveys also reflect the bias at the time. The race variable for the earliest studies did not stand alone, but instead was incorporated into the economic status variable, assigned by interviewers, which served as both an economic and social class measure. Black Americans were identified as “Cl” (for “Colored”) in NORC and “N”(for “Negro”) in Roper Organization polls. The inherent bias against Black Americans in early polling is evident in the lack of economic variables assigned to Blacks. Even the wealthiest of Black Americans were categorized economically solely on their race. In some cases, NORC used economic variables that sorted whites into five possible categories, the lowest of which was “OR-W” for “On Relief.” Black Americans were classified as “Cl” or “OR-Cl”. Organizations began to break out race into separate question in the 1940s. Eventually, organizations also added an “other” race category: in 1946 by Roper, in 1958 by Gallup, and 1963 by NORC.

The adoption of probability sampling in the 1950s greatly enhanced the validity and reliability of survey data. However, while large-scale government surveys and some academic surveys continued to use large sample sizes, public polls had tighter budgets and needed to be fielded more quickly in order to be responsive to changing public attitudes on evolving public issues. The typical sample size of a national probability-based sample in polling was 1,000-1,500 respondents, and as a result, analyses of subgroups were (and remain) difficult due to small sample sizes of these groups. Further, as a result of the increased expense of probability polling and insufficient investment in oversamples, data provided limited opportunities for analyzing racial groups. State-level polls were often even smaller, and those states with small Black populations could end up with only a handful of Black respondents.